And you will be the leader of a big old band

Many people coming from miles around

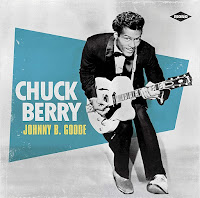

To hear you play your music when the sun go down.’”—American singer-songwriter Chuck Berry (1926-2017), “Johnny B. Goode,” from his LP Berry Is On Top (1959)

Sixty-five years ago today, “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry was released. It was not the first hit for the rock ‘n’ roller (that was “Maybellene,”

which came out three years before), and other songs in his catalog went higher on the charts (such as his immediately prior single, “Sweet Little Sixteen”).

Nonetheless, “Johnny B. Goode” has a definite place in

rock ‘n’ roll history. Garth Cartwright’s discussion of the tune, in his

“Life of a Song” column for The Financial Times this past December,

claims that it is “thought to be the first song in popular music history in

which the singer celebrates their own success.”

From several decades of past experience as a librarian,

I can tell you, Faithful Reader: beware of anything that purports to be “the

first” in popular culture. Somebody somewhere has a vested in claiming he is

the biggest, first, greatest, etc. As the Gershwin song goes, it ain’t

necessarily so.

I would have lifted an eyebrow, though perhaps have

not disputed the point altogether, if Cartwright had asserted that it was the

first such instance in rock ‘n’ roll history, since that genre was only a few

years old at this point.

But “popular music history”—i.e., not just rock ‘n’

roll but also incorporating jazz and the Great American Songbook—wellllll…That’s

all I can say, although it’s a good thing that Cartwright employed the useful

get-out-of-jail-card phrase, “thought to be.”

So let’s say that Berry helped popularize the notion

of the stardom promised by rock ‘n’ roll—a concept that would be trumpeted

later in Cynthia Weill and Barry Mann’s “On Broadway,” and Bruce Springsteen’s “Rosalita

(Come Out Tonight).” (The Boss advises the title character to tell her father, “this

is his last chance to get his daughter in a fine romance/Because a record

company, Rosie, just gave me a big advance”).

Berry’s hit also popularized what became just as common as a singer’s braggadocio: word play in rock ‘n’ roll.

Start with this

song’s title. Hearing a DJ say it on the air for the first time, a listener

would be sure that it was an adult’s admonition to a tyke: “Johnny Be Good.” But

“Goode” was actually a tip of the hat to the singer’s origins: Goode Avenue in

St. Louis, MO.

Before long, others wanted to get in on the act,

including (but by no means limited to):

*The Beatles: What did adults think they heard

when the group’s name was first uttered? “The Beetles” (itself a nod to The

Crickets, the backing musicians for Paul McCartney’s musical hero, Buddy

Holly);

*The Monkees: An American Beatles knockoff not

just in the long hairstyles sported by this quartet, but in how the band name

was a play on words (a fact not readily apparent to some clueless adults,

including—as Micky Dolenz discovered when he got his hands on the group’s FBI’s files—a G-Man who referred to them as “The Monkeys”); and,

*Crosby, Stills and Nash, who styled their hit “Suite:

Judy Blue Eyes” as a pun on “Sweet Judy Blue Eyes,” a reference to Stephen

Stills’ former girlfriend Judy Collins.

I haven’t even assessed the song’s musical influence,

but that’s pretty well known, isn’t it? After all, no less an authority than

Bob Seger, in “Rock 'n' Roll Never Forgets,” correctly observed, “All of Chuck's

children are out there playing his licks”—as true today as it was in 1976 or,

for that matter, 1958.