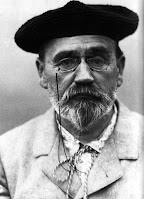

Jan. 13, 1898—French novelist and journalist Émile Zola had raised the hackles of censors before with his often sexually frank novels.

But nothing matched the intensity of the storm that swept over him when, in a ringing front-page open letter to the President of the French republic published in the socialist the Socialist newspaper L'Aurore, he charged that army Capt. Alfred Dreyfus had been falsely charged with espionage—and that embarrassed military and political leaders had continued to cover up the miscarriage of justice after learning of their mistake.

Largely apolitical until this time, Zola learned a

couple of months before the details of the case from a friend of Lieutenant

Colonel Georges Picquart, the head of French intelligence—who, for his efforts

to reopen the investigation and expose the real spy who had handed a military

document to Germany, Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, had found himself reassigned

to Tunisia.

Zola not only brought to wide public attention the grave

injustice done to Dreyfus, who had been stripped of his command and imprisoned

in a penal colony on Devil’s Island, but issued a prescient warning about the factor

that had made the captain a scapegoat: the “odious anti-Semitism, of which the

great liberal France of human rights will die, if she is not cured of it.”

By naming the culprits in the affair—not only Esterhazy

but top generals and three handwriting experts who had perpetuated the coverup—Zola

took a calculated risk, daring the authorities to prosecute him under

defamation laws so that the full details of the case could be exposed at trial.

It would be hard to overestimate the impact of the

Dreyfus Affair on French political, military, media, cultural, and religious

institutions. For a dozen years, the nation was consumed by each twist in this

controversy, dividing into roughly two factions: the anti-Dreyfusards, who

tended to be monarchist and Roman Catholics; and the Dreyfusards, with a more

republican and secular orientation.

Even among the unusual figures in this controversy,

Zola stood out. In 20 novels over a four-decade career, he proposed a school of

writing that came to be called naturalism, in which characters are observed as

if under a microscope, less obedient to free will than to instincts such as

greed and lust. His frankness on the latter score, whether through a prostitute

in Nana or a pair of adulterous lovers who murder a husband in Therese

Raquin, caused sensations.

Zola could be unappreciative or dismissive of people

who influenced or aided him. Writing about Gustave Flaubert, he criticized him as

“a shameless joker, a paradoxical thinker, an impertinent romantic who made my

head spin for hours with a deluge of astonishing theories,” while contrasting Flaubert’s

painstaking writing process with his own, which was “forged on the terrible

anvil of daily deadlines."

When a British book publisher was prosecuted for

obscenity for translating novels by Zola, the writer not only didn’t support

his friend but told a reporter that a successful prosecution might be better for

him, as readers could hunt them down in the original French rather than endure

cheap translations into English.

Assessing Zola in a retrospective history of the first decade of Masterpiece

Theatre (which featured an adaptation of Therese Raquin), host Alistair Cooke assailed the author’s “exhibitionism” and

flair for self-dramatization. Although there was some truth in the characterization,

Zola also truly did expose himself to real legal and physical danger with “J’Accuse.”

He not only was indicted for defamation, as he

expected, but also was exposed to death threats provoked by the vitriolic

anti-Dreyfusard press. After being condemned to fines and a year-long sentence

of imprisonment, he fled to England, where he stayed until the charges against

him were dismissed.

Captain Dreyfus would not be reinstated until four

years after Zola’s death in 1902. Nevertheless, the novelist died still firmly believing in perhaps the most famous quote from his expose of this shameful

chapter in the life of France: “Truth is on the march, and nothing will stop it."

The dozen years of the Dreyfus Affair were a mad swirl

of events in France’s Third Republic: “intrigues, fraud, resignation and

overthrow of ministers and the parliament, riots, assassinations, suicides, the

attempt of a coup d’état and an alarmingly widespread anti-Semitism,” in the

words of a 2015 post from the Europeana Newspapers blog.

It was a mark of the tumult of the time that even Zola’s

death in his home became swallowed up in the dizzying news cycle. Rumors

circulated that he had been murdered by anti-Dreyfusard fanatics.

The results of the inquest indicated carbon-monoxide

poisoning, but the public was told simply that he had died of natural causes.

It would not be until 1927 that an anti-Dreyfusard stove-fitting contractor allegedly

confessed on his deathbed to have blocked up the chimney while mending the roof,

and not until 1953—a full half-century after Zola’s death—that a French

newspaper published this account. After so much time, it may not be possible to

fully establish the truth of the account.

(For more on Zola’s still-contested death, see this 2015 blog post from Dr. Gabe Mirkin and Richard Cavendish’s September

2002 account in History Today.)

“J’Accuse” marked the turning point in the larger uproar

of the Dreyfus affair, which itself represented a hinge moment in Western

history. Its repercussions were long-lasting, even global, as it:

*contributed to the formal separation of church and

state in 1905, to prevent any repetition of the virulent anti-Semitism

displayed by many French Catholics in the controversy;

*convinced Theodor Herzl that, even after consistent, enduring

attempts at assimilation in relatively liberal France, European Jews were not

safe, and spurred him to advocate for Jewish immigration to Palestine in an

attempt to create their own homeland;

*foreshadowed, through the interaction of government,

mass media, and ephemera, the modern news cycle of nonstop ideological

firestorms;

*paralleled the 21st-century divide between secular, urban liberals and more religiously orthodox, rural conservatives;

*inspired intellectual crusades against judicial verdicts

perceived as blighted by ideology or prejudice—including, in the United States,

the Sacco and Vanzetti, Alger Hiss, and Rosenberg trials.

Even at the turn of the 20th century, film directors recognized the dramatic impact of the Dreyfus Affair, with French filmmaker Georges Méliès staging and shooting 11 one-minute silent reenactments of the trial. In one of the first cases of government censorship of motion pictures, the French government banned further exhibition of Melies’ pioneering film effort. (Indeed, that ban on cinematic treatments of the affair would remain in effect until 1950.)

That did not stop other nations’ filmmakers from

depicting the scandal, including Richard Oswald’s Dreyfus (Germany,

1930); William Dieterle’s The Life of Emile Zola (U.S., 1937); José

Ferrer’s I Accuse! (U.K.–U.S., 1958); and Roman Polanski’s An Officer

and a Spy (J’Accuse) (France, 2019).

(For a useful summary of many of these films, see Thomas Doherty's Fall 2020 overview in Cineaste Magazine.)

No comments:

Post a Comment