Fifty years ago this month, a 23-year-old rock ‘n’ roller, crafting songs more than an hour outside New York City, sought in his first album to gain a national following and shake what an earlier New Jersey singer would call “these little town blues.”

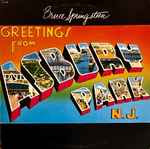

At that time, despite the commitment of the Columbia Records label, Bruce Springsteen did not measure up to initial expectations with Greetings from Asbury Park. Only 25,000 records were sold then—the result of absent guitar solos, failure to fit into then-current pop music trends, a sound that lacked the tightness and electricity of his live shows, and a musician who had not found his unique voice yet.

But two and a half years later, when Born to Run gave Springsteen an across-the-board radio breakthrough at last, fans like me flocked to record stores for his two other albums to that point, including Greetings.

Ensuring the collection’s continuing longevity, other artists would cover several of its songs, and Springsteen would incorporate all 11 songs into his epic concerts over the following half-century, with varying degrees of frequency.

In a David Brooks piece 11 years ago, the New York Times columnist cited Springsteen as exemplifying “artists who have the widest global purchase [being] also the ones who have created the most local and distinctive story landscapes.

The work in which the musician began to create that landscape was Greetings—with the album titled and designed like a postcard, unapologetically proclaiming the musician’s New Jersey roots.

Isolation from music centers like New York, Los Angeles, Nashville, and Detroit both hurt and helped Springsteen. It meant that he would start without a network of influencers and fellow musicians who could have boosted his career.

However, plying his trade as a rising bar-band presence, he would not be unduly limited by a single genre, and could gauge, on a micro scale, how to bring audiences to their feet again and again.

Springsteen’s firm embrace of his Jersey Shore roots did more than just mark him as a unique musical personality. It also gave exposure to other local musicians, such as good friend and future bandmate “Miami Steve” Van Zandt and “Southside Johnny” Lyon, and ensured that the fate of Asbury Park—a shore town that had fallen on hard times—would not be forgotten by those who encountered the community through the music.

To their credit, Columbia Record executives John Hammond and Clive Davis recognized that Springsteen had talent. But they weren’t sure what to make of it, or him.

The dominant template for the music scene of the time was the confessional singer-songwriter movement—not just Bob Dylan, but newly ascendant stars like James Taylor, Carly Simon, Joni Mitchell, and Jackson Browne. Coming from the folk music scene, they could operate solo with a single instrument—a guitar or piano.

All songs have to start from somewhere, and Springsteen’s came together in particularly unprepossessing conditions.

Several of them were written on a piano in an abandoned second-floor beauty salon in Asbury Park, while sessions took place at 914 Studios in Blauvelt, N.Y. There, Springsteen and his musicians could record cheaply and, because the studio was adjacent to a Greek diner, eat cheaply, too.

(In contrast to later Springsteen albums, there was little time to perfect the product—only two weeks for the 11 songs, unlike for the marathon Born to Run sessions two years later, which took 14 months—with six devoted to the title tune itself.)

Hammond, the legendary record producer who had signed such acts as Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, and Leonard Cohen, wanted what he heard at Springsteen’s audition: a solo act. So did Springsteen’s manager and producer at the time, Mike Appel.

So Springsteen could forget about having his band as an integral part of his first release. He was lucky he could get any of them onto half of the songs originally submitted. (Even best friend “Miami Steve” only got onto one song, “Lost in the Flood”—Springsteen would be the lone electric guitar player on the album.)

Greetings from Asbury Park, then, wasn’t the album Springsteen wanted to make but the one he could make.

Clive Davis, then head of Columbia Records, rejected Springsteen’s first group of songs, insisting that he couldn’t hear a hit in any of them.

In response, the two songs that Springsteen came up with, “Blinded by the Light” and “Spirit in the Night,” introduced into the mix Clarence “Big Man” Clemons, the charismatic saxophonist who would become the indispensable on-stage foil for “The Boss” for the next three decades.

Clarence’s “cool saxophone,” Springsteen wrote in his 2016 memoir, Born to Run, “made a big difference”: “This was the most fully realized version of sound that I had in my head that I would get on my first album.

Still, for all the pleasure that Springsteen took in seeing his work out in the market, Greetings faced significant headwinds. Even with the likes of Dylan and Neil Young paving the way, Springsteen’s vocals were unusual for these times—and it could be tough for some listeners to get past his raspy tones in order to decipher his lyrics about boardwalk bohemians, dreamers, hangers-on, and misfits.

Moreover, the label’s “New Dylan” label did no favors for Springsteen. It opened him up to criticism that he was derivative, a creature of hype, while ignoring the host of other influences that would soon become apparent in his work: Elvis, Chuck Berry, Gary “U.S.” Bonds, Roy Orbison, Van Morrison, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Hank Williams, Pete Seeger, and Phil Spector.

Nevertheless, for those who came to the album and its creator later, there was something distinctive about what Wall Street Journal contributor Marc Myers termed earlier this month Springsteen’s “brand of machine-guy storytelling peppered with unmoored characters and seedy imagery.” It was raw and alive.

The LP just needed the

conditions that would be in place for Born to Run two years later: a

band of brothers forged under fire—their leader’s pushing himself and them to

their creative and physical limits—and the desperate sense, in the studio and

even in the lyrics, that life was riding on this moment.

For many of us venturing outside the state, The Boss was giving us something we didn't have before: not an embattled identity but a source of pride. And, instead of Tony Soprano's "family" of not-so-good-fellas or the reality-show party animals of "Jersey Shore," Springsteen was demonstrating the wonders that could be created from local color.

No comments:

Post a Comment