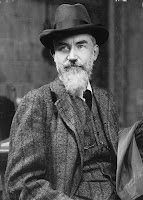

Dec. 28, 1923—Even though critics had derided the most recent play of George Bernard Shaw as too verbose and long, the Anglo-Irish playwright’s new comedy-drama was in much the same vein: Saint Joan, which premiered at New York’s Garrick Theatre.

Instead of driving audiences away, however, the six-act (with epilogue), 3½ hour comedy-drama-historical epic about Joan of Arc proved to be a great success. It was acclaimed as the capstone of his nearly three-decade career as a dramatist, propelling him towards the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925.

At the same time, this success boosted the faith of the playwright in—as well as the box-office take of— the most influential producing company of the 1920s and 1930s, the Theatre Guild, which became the major American sponsor of new work by not only Shaw but also emerging homegrown dramatists such as Eugene O’Neill, Philip Barry, Maxwell Anderson, Robert Sherwood, Sidney Howard, and William Saroyan.

The Guild—which pioneered the subscription plan as a means of assuring a constant stream of avid playgoers more disposed to experimental, challenging fare—had done well with Shaw's Heartbreak House in 1920. But with Back to Methusaleh, a five-play series that represented the closest the playwright came to science fiction, the company lost $20,000—a failure that Shaw attributed to the Guild's management rather than to himself.

In contrast, the Guild's board of directors was more enthusiastic about Saint Joan. But, as the play approached its premiere, the board became concerned that the same issues that plagued its predecessor would hinder the success of this new entry.

More was riding on the American success of the dramatist whose wife playfully nicknamed "The Genius." The London production of Saint Joan, starring one of Shaw’s favorite actresses, Sybil Thorndike, ended up being delayed until March 1924, so the Guild’s staging became the de facto world premiere, and news about its effectiveness would be transmitted overseas.

As was his wont, Shaw conducted his business with the American theater from across the Atlantic Ocean.

Despite the importance of America to Shaw’s long-term commercial viability (it represented his largest source of income from 1894 to his death in 1950), the playwright did not visit the nation until 1933, and in general regarded it, according to L. W. Conolly’s Bernard Shaw on the American Stage, with “a toxic mix of contempt and mockery."

Alhough Katharine Cornell, fast acquiring a reputation as one of the greatest American stage actresses, passed on this initial production, the Guild board of directors ended up delighted with the blue-eyed Brooklyn beauty who took on the title role: Winifred Lenihan, who made of it a career triumph.

First after the dress rehearsal, then again after opening night, the Guild noticed that some attendees, especially from the suburbs, were departing early. Their initial cables urged Shaw to cut some of the dialogue to reduce that, but they received no reply.

Only after the company management prevailed on the 25-year-old Lenihan to send her own cable with a similar request did the playwright respond. They might not have wished they had sent all these messages when they saw Shaw's follow-up.

To Ms. Lenihan, the playwright’s cable was short and ironic: “THE GUILD IS SENDING ME TELEGRAMS IN YOUR NAME. PAY NO ATTENTION TO THEM.” The organization’s management must have winced at his longer, more lacerating letter to them: “You ought to be ashamed of yourselves for getting a young actress into trouble with an author like that…. You have wasted a whole morning for me with your panic-stricken nonsense, confound you!”

In the end, it didn’t matter: the public ignored reviewers who complained about the length by purchasing tickets. Despite his waspish transatlantic exchanges with the Theatre Guild's management, Shaw elected to stay with it as the principal American agent for his plays, with a total of 15 plays under its aegis.

Although Shaw wrote over 60 plays, Saint Joan ranks among his most popular, probably trailing only Pygmalion (which has the benefit of not only inspiring the musical My Fair Lady, but is also logistically easier to mount, with fewer characters and sets).

Over the centuries, Joan has provided fodder for a lengthy parade of novelists and dramatists, including William Shakespeare, Voltaire, Friedrich Schiller, Mark Twain, Bertolt Brecht, Jean Anouilh, and others. But it’s Shaw’s depiction that has captured the popular imagination the most.

In the early postwar period, Saint Joan exerted an unusual appeal for colonial audiences that, like France in Joan’s time, was feeling the stirrings of nationalism.

Yet even then, in the McCarthy period, it was also seen as a broadside against intolerance, and more recently has appealed to those who sympathize with her plight at the hands of men who hope to squash what Shaw ironically termed “unwomanly and insufferable presumption.”

It is a curious fact of Joan of Arc’s posthumous appeal that two religious skeptics like Twain and Shaw could be so powerfully drawn to the story of this saint. Leave aside the odd contention, in Shaw’s preface to the play, that Joan was “one of the first Protestant martyrs.”

Remember instead: the recollection of Theatre Guild founder Lawrence Langner, in his 1963 memoir, GBS and the Lunatic, that Shaw attributed the enormous speed with which he wrote the play to Joan herself: “As I wrote, she guided my hand, and the words came tumbling out at such a speed that my pen rushed across the paper and I could barely write fast enough to put them down."

In 1934, Shaw predicted correctly, “It is quite likely that sixty years hence, every great English and American actress will have a shot at ‘Saint Joan,’ just as every great actor will have a shot at Hamlet.”

Among those who have played Shaw’s version of the

Maid of Orleans: Katharine Cornell (catching it on the rebound), Wendy Hiller,

Zoe Atkins, Judi Dench, Uta Hagen, Joan Plowright, Lynn Redgrave, and Kim

Stanley.

I myself have seen two productions: one at Manhattan's Paley Center for Media, a 1967 "Hallmark Hall of Fame" TV presentation starring Genevieve Bujold; the other a 2018 Manhattan Theatre Club performance with Condola Rashad in the title role.

Both productions shortened the text—an eventuality that Shaw dourly predicted in the preface to the play, when he noted that "well intentioned but disastrous counsellors" would have their way "when I am no longer in control of the performing rights."

No comments:

Post a Comment