June 2, 1967—The Beatles’ LP Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released on this date in the

United States, could, in retrospect, also have been titled Hello, Goodbye.

June 2, 1967—The Beatles’ LP Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released on this date in the

United States, could, in retrospect, also have been titled Hello, Goodbye.

With their eighth studio album, the Fab Four were

bidding hello to identical album track listings in both the U.S. and United

Kingdom; to album artwork (including gatefolds) as iconic and ironic as the pop

art of the time; and to the upcoming Summer of Love. On the other hand, with the mustaches

that ended their clean-cut image, with the drug use that was driving a wedge

within the group, and with their concentration on elaborate studio work at the

expense of the touring that brought them together even as it extended their fan

base, they were saying goodbye to their innocence.

Then as now, Sgt.

Pepper’s overwhelming ambition and sound invited hype. Critic Kenneth Tynan styled the

work “a decisive moment in the history of Western civilization,” while Rolling Stone has placed it atop its

list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

Much of the LP’s

exalted status derives from something a bit overstated: its position as a landmark

pop “concept album.” As Jody Rosen noted in a Slate article five years ago,

the last notion was “demonstrably false.” It was not merely that the “concept”

overarching this album—the creation of an alternative “band” playing its own

songs—rested on the thinnest of conceits, but that other artists had gotten

there first—e.g., Frank Sinatra and the Beach Boys. In fact, John Lennon claimed that none of his songs

on the album were written with the “concept” in mind.

With that in mind, it’s still the case that Sgt. Pepper forms a unified whole, a

dazzling example of what a pop album could be. The unity derives, paradoxically,

from diversity, a mélange of different musical styles—not only blues and rock,

but also jazz, Indian music, classical, and even England’s music hall

tradition. ''They were competing with themselves, wanting to get better all the

time,'' said producer George Martin

20 years later. Their monster success meant they had unlimited time at the

famous Abbey Road Studios, and they spent hours there that were considered

astonishing in the grind-them-out atmosphere of '60s pop music.

They were all melded together in an attempt to create

sounds that simple rock ‘n’ roll—the new style the group had learned as

Liverpool teens only a decade before—had seldom, if ever, heard. “A Day in the

Life,” with its massive orchestration, was only the most prominent example.

Ingenious in its own way were the sounds employed

for “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite.” In prior albums, the group had

challenged Martin to come up with increasingly experimental sounds. Now, Lennon

told Martin that for this song inspired by an old circus poster, he wanted to "smell

the sawdust on the floor" when he heard the record.

To convey a circus-like atmosphere, according to

engineer Geoff Emerick, Martin pumped a harmonium for a full four hours until

he collapsed. When he couldn’t find a calliope, he got hold of calliope tapes

of marches by John Philip Sousa, chopped them into small sections, and had

Emerick piece the whole thing together in random order.

After their breakup, the Beatles, to a man,

agreed that they were most cohesive in the Sgt.

Pepper sessions. Indeed, several tunes feature some of the most felicitous

moments in the entire Lennon-McCartney partnership, including:

·

* * Lennon’s jaunty rejoinder to Paul McCartney’s

“Getting Better All the Time” (“It can’t get no worse”);

·

* Lennon’s even snarkier answer to the

romantic Paul’s question on “With a Little Help From My Friends,” “Do you

believe in a love at first sight?” (“Yes, I’m certain that it happens all the

time”); and

·

* McCartney’s “woke up, got out of bed…”

song fragment to fill an audio hole in the middle of “A Day in the Life”.

After all of those good feelings of collaboration—present,

for instance, in just about every groove of “With a Little Help From My Friends”—there

were still ill winds blowing through the recording sessions that would

undermine the group’s unity in less than a year. The band's growing marginalization

of manager Brian Epstein, for instance, worsened his already considerable

insecurity, and his death two months after the album’s release would plunge the quartet into shock, grief, guilt, and eventual bickering over future financial

directions.

Lennon’s drug use was also getting to be a far

greater problem, as he downed amphetamines to wake up, took pot throughout the

day, and, at times, mistook tabs of LSD for the sleeping pills that lay beside them at his bedside. Sometimes he would be AWOL for tracks by McCartney

or George Harrison. Toward the end of a March session recording “Getting Better”

and “Lovely Rita,” Lennon began to trip out right at the microphone. That

night, McCartney, having brought his friend home, did something he’d previously

resisted doing—drop acid—in order to keep his collaborator company.

“I’d love to turn you on,” indeed.

That brings up, inevitably, the question of drugs on

the album. The BBC banned the LP from the airwaves because of the

aforementioned line from “A Day in the Life” as well as the acronym implicit in

the title, “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.” In the case of the latter, however,

Lennon pointed instead to a drawing made by his son Julian in nursery school

that the boy referred to as “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.” The images, the

songwriter insisted, derived from Lewis Carroll—not the only time in 1967 that a rock

classic would be based on the surreal fantasies of the Victorian children’s

book writer. (See Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit.”)

McCartney might have been the driving force behind

the overall concept, production and even album design of Sgt. Pepper, but it remains impossible for me to imagine the LP

without Lennon’s contribution. The Joycean wordplay of his lyrics served as a

nice balance to McCartney’s often trite ones, and his phantasmagorical visions

in “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” and “A Day in the Life” opened up future

avenues in acid and progressive rock.

“It would be easy to dismiss Sgt. Pepper as rock’s

most overrated album if it weren’t the Beatles’ most underrated group effort,”

writes NPR critic Tim Riley in his 2011 biography, Lennon—The Man, the Myth, the Music—the Definitive Life. “Almost

everything you need to know about the band lies in its grooves, and it holds

the best and worst of what they’re most famous for.”

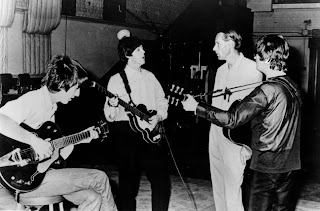

(The photo accompanying this post was taken in 1966, the year that the Beatles entered the Abbey Road Studio to record Sgt.Pepper. The only band member missing from this publicity shot with George Martin is Ringo Starr.)

No comments:

Post a Comment