“Every court has its diva. Silvio Santamaria, 250

pounds, gel-slicked-back jetblack hair, former boxer, Jesuit seminarian, father

of thirteen children, Knight of Malta, adviser to the Vatican on international

law and even occasional guest advocatus

diabolic in canonization cases….He was brilliant, with a wit as caustic as

drain cleaner; good company if you were in his camp and look out if you

weren't. Silvio Santamaria didn't take yes for an answer. He didn't disagree—he

violently opposed. Didn't demur—he went for your throat. Didn't

nitpick—disemboweled you and flossed his teeth with your intestines.

First-timers appearing before the Court for oral argument had been known to wet

their pants and even faint under his withering questions and commentary. His

written dissents were of the type described by the press as ‘blistering’ or

‘stinging’….He gave fiery—and rather good—speeches that had his audiences

stomping on the floor and standing up on their chairs calling for—demanding!—a

new Inquisition.”— Christopher Buckley, Supreme Courtship (2008)

“Every court has its diva. Silvio Santamaria, 250

pounds, gel-slicked-back jetblack hair, former boxer, Jesuit seminarian, father

of thirteen children, Knight of Malta, adviser to the Vatican on international

law and even occasional guest advocatus

diabolic in canonization cases….He was brilliant, with a wit as caustic as

drain cleaner; good company if you were in his camp and look out if you

weren't. Silvio Santamaria didn't take yes for an answer. He didn't disagree—he

violently opposed. Didn't demur—he went for your throat. Didn't

nitpick—disemboweled you and flossed his teeth with your intestines.

First-timers appearing before the Court for oral argument had been known to wet

their pants and even faint under his withering questions and commentary. His

written dissents were of the type described by the press as ‘blistering’ or

‘stinging’….He gave fiery—and rather good—speeches that had his audiences

stomping on the floor and standing up on their chairs calling for—demanding!—a

new Inquisition.”— Christopher Buckley, Supreme Courtship (2008)

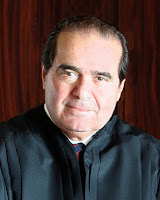

Sure, Hatchette Book Group included in this novel one

of those pro forma “any resemblance to actual events, persons,” etc., disclaimers

to ward off litigious objects of fictional derision. But really, can there be

any doubt whom master satirist Christopher Buckley had in mind in his acidic portrait of Associate Justice Silvio

Santamaria? I can’t remember him leaving such unmistakable clues to any other real-life

counterpart. (Even in No Way To Treat a

First Lady, he gave his assertive, high-decibel First Lady with a wayward hubby—“Lady

BethMac” to the tabloids—looks that inspired comparison to Catherine

Zeta-Jones.)

But that “diva” line alone is a dead giveaway that Buckley

has within his sights Antonin Scalia,

who shares with fellow Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg a love of

opera—and, as far as ideology goes, very little else.

These days, Scalia appears ready to break out at any

minute into a number from Verdi’s Otello—“Dio!

mi potevi scagliar tutti i mali!” ("God, you could have thrown every evil

at me”) — in which the title character, in the midst of torment, asks the

Almighty why he is being afflicted in this manner.

Pointed dissents can be excellent means for some

justices to achieve immortality, as the cases of Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes

Jr. and John Marshall Harlan. But Scalia’s dissents can only be measured on a different

order of magnitude: the Richter scale. They create not footsteps in the sand

for later justices to follow, but entire craters where working relationships and

conservative influence crumble.

You don’t win friends and influence people—prerequisites

to writing majority opinions—if you essentially publicly call out colleagues on

the high court as idiots—especially in decisions that will be read by hundreds

of thousands of lawyers worldwide for generations to come.

As the latest term of the Supreme Court of the

United States (SCOTUS) ends, Scalia sounds not merely encircled but friendless

and hysterical. The 5-4 majority that sanctioned same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges, he proclaimed,

amounted to a “judicial putsch.” Not done with invidious comparisons with

Nazis, he went after the decision’s style, which he pronounced “as pretentious

as its content is egotistic.”

Justice Anthony Kennedy, author of the majority

opinion, surely felt his ears burn when he heard this footnote read in Scalia’s

dissent: “If, even as the price to be paid for a fifth vote, I ever joined an

opinion for the court that began: ‘The Constitution promises liberty to all

within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow

persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity,’ I would

hide my head in a bag.”

Give Scalia this: that sentence from Kennedy’s

opinion does slip, slide, and flop

around some. But Kennedy, for all his offenses against sound and meaning, also

learned a skill in elementary school that has eluded Scalia in three decades on

the high court: how to get to five, the magic number needed to achieve a

majority.

Chief Justice John Roberts has learned not only this elementary arithmetic, but also

astronomy, the more advanced discipline of bringing distant objects into close

view. He may not have turned out to be the honest umpire he cited as his ideal

at his Senate confirmation hearings, but he has shown definite signs of knowing

how far he can go before the legitimacy of the court’s rulings is questioned.

This long game is lost on Scalia. Oddly enough, one

of America’s most famous opera buffs is politically and personally tone deaf. It

seems never to have occurred to Scalia that, far from buckling under to a solid

liberal wing of the court, Roberts might be jumping aboard the majority express,

only to hijack it for his own purposes.

The chief’s initial preservation of Obamacare back

in 2012, for instance, was built on the premise that the health care individual

mandate was a tax—a notion that the administration was not keen on accepting.

Moreover, by refusing to strangle it while still in its toddling stage, he gave the

President time to proceed with the rollout of the program’s Website, a disaster

that damaged Obamacare’s reputation and Obama’s approval ratings.

But Scalia could see none of this, implicitly taking

his boss to task in a dissent for saving the controversial legislation by transforming it through

reinterpretation: “We should start calling this law SCOTUScare.”

These are just the latest in a series of splenetic

sputterings about colleagues’ opinions. There’s a whole Website devoted to

these “Scalia-Isms,” in fact—and I

believe it gets nowhere close to the full number. That’s because Scalia is to

judicial invective what Niagara Falls is to water.

After awhile, the name-calling begins to blur together, in a

crazy kind of way. In fact, Tim Murphy of Mother

Jones invented a “Scalia Insult Generator” that allows readers to mash these up and create new ones of

their own.

Right-wingers, enthralled by the tenor booming out

these insults, have lost sight of how deeply

counterproductive these are. It’s one thing to write, as Scalia did

a few years ago about a Sixth Amendment majority opinion by Sonia Sotomayor,

that she had rendered the high court “the obfuscator of last resort”—she was,

after all, appointed by a liberal Democrat and has voted in a way that could

hardly have ever displeased the President.

But it’s another thing to go after fellow Republican appointees. Roberts

chuckled for the cameras when Scalia read aloud the ‘SCOTUScare” barb. But other

justices tapped for the court by conservative GOP Presidents have not been as equanimous.

The most consequential was Sandra Day O’Connor. Prior

to the 1989 Webster case involving abortion,

she had written critically about Roe v.

Wade. The particular circumstances of Webster,

she noted in the majority decision, did not warrant a more definitive ruling at

that point, but there would be time for such a reconsideration.

Annoyed that she had not taken the bull by the horns immediately, Scalia, in a separate opinion, assailed O’Connor’s position as “irrational”

and one that “cannot be taken seriously.” As Linda Greenhouse demonstrated in a blog piece for The New York Times four years ago, the court’s only female justice at the time--and the one whose swing vote would later devolve upon Kennedy--showed what she

thought of that remark three years later in Planned

Parenthood v. Casey, when she provided the critical fifth vote to leave Roe undisturbed.

For the sake of a couple of peevish one-liners,

Scalia had alienated the justice who could have overturned a decision that had

been coming under increasing political and intellectual assault. He had lost a

critical battle in the abortion battle he cared so much about.

Kennedy is another matter. His stances on abortion and gay rights notwithstanding, there is very little else separating his conservative opinions from Scalia's. (Gays and lesbians better not cheer that loudly for Kennedy's latest opinion on same-sex marriage--if they yell too vigorously, they'll be breathing some of the air likely to increase in the wake of the justice's vote with--again!--a 5-4 majority to strike down the Environmental Protection Agency's national standards for mercury pollutants from power plants.)

It shouldn't take that much to turn Kennedy. An example of how Scalia could have done so was provided by his onetime Court colleague William Brennan. Even when Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan turned the Supreme Court decisively away from the liberal rulings of the Warren Court with new appointees, Brennan continued to cobble together improbable majorities through legendary persuasive powers.

Kennedy is another matter. His stances on abortion and gay rights notwithstanding, there is very little else separating his conservative opinions from Scalia's. (Gays and lesbians better not cheer that loudly for Kennedy's latest opinion on same-sex marriage--if they yell too vigorously, they'll be breathing some of the air likely to increase in the wake of the justice's vote with--again!--a 5-4 majority to strike down the Environmental Protection Agency's national standards for mercury pollutants from power plants.)

It shouldn't take that much to turn Kennedy. An example of how Scalia could have done so was provided by his onetime Court colleague William Brennan. Even when Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan turned the Supreme Court decisively away from the liberal rulings of the Warren Court with new appointees, Brennan continued to cobble together improbable majorities through legendary persuasive powers.

Yet Scalia remained unchastened by his defeats. As New York Magazine’s Jennifer Senior noted recently, “the more isolated he

gets, the more extravagant his rhetoric becomes.”

Roberts seems to want to become a 21st-century

counterpart to John Marshall, a Chief Justice who, through intellect and power

of personality, aims to block a President of a different party who does not

share his view of the role of the federal government. In his health-care

rulings, Roberts has also absorbed one of the principal lessons of the career

of that wily predecessor: pick your fights when it matters most, and only then,

lest you threaten the legitimacy of the court of last resort.

Scalia, on the other hand, seems to be taking the

path trod by Samuel Chase, Marshall’s fellow Federalist appointee to the bench.

The blunt Associate Justice, dismayed by the election of Thomas Jefferson, gave

a Scalia-like warning that America was descending into “mobocracy.” For these

and other pronouncements less judicial than political, Jefferson encouraged Senate impeachment of Chase.

While Chase survived the maneuver, his reputation did not.

He is now known to history as an intellectually gifted justice who spoiled his

legacy through nakedly partisan stances and intemperate language.

Sound familiar?

No comments:

Post a Comment