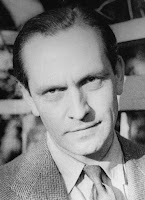

“What I enjoy is working on a scene until I finally get it right. It's fun to know you're hitting it. There are advantages in being in a long run. You should see plays after they've been around for a while if you want to see the best performances…. The actors are more relaxed in their parts. When I first consider a part, I find myself judging the play as a whole. Simultaneously, I try to decide whether I can play the part, whether it's dramatically interesting, whether I feel I can make it make sense. It's a mistake, I think, to go for parts, as some actors do, instead of for the play as a whole. I'll never do a part in a play or a picture that makes me lose my self-respect…. In a way, though, I've liked everything I've been in. I'm kind of a dimwit. I just like to act.”—American screen and stage actor Fredric March (1897-1975), quoted in Lillian Ross and Helen Ross, The Player: A Profile of an Art (1962)

Two-time Oscar-winning actor Fredric March was

born Ernest Frederick McIntyre Bickelin in Racine, Wisc., 125 years ago today. Over

a long career on the big screen and the stage, he seldom if ever had to worry

about losing his “self-respect.”

It wasn’t enough that the enormously versatile star

could do comedy (Nothing Sacred, I Married a Witch) as well as tragedy

(the original A Star is Born, Anna Karenina), that his Academy

Award performances in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and The Best Years of

Our Lives still stand the test of time, or that he segued expertly from a matinee

idol of the Thirties and Forties into an adept ensemble player from the Fifties

to his death in 1975.

No, when it came time for directors to find a leading

man unafraid to take on two highly demanding properties by Pulitzer

Prize-winning playwrights—Thornton Wilder (The Skin of Our Teeth) and

Eugene O’Neill (Long Day's Journey Into Night)—they turned to March. He

did not let them—or audiences—down.

No comments:

Post a Comment