Thursday, December 31, 2020

Quote of the Day (Edith Wharton, on New Year’s Day in the 1870s)

Movie Quote of the Day (‘Holiday,’ With a New Year’s Eve Party for ‘Very Unimportant People’)

Linda Seton [played by Katharine Hepburn]: [Making introductions] “My brother Ned—Mr. and Mrs. Potter—they're friends of Johnny's.”

Mrs. Susan Elliott Potter [played

by Jean Dixon]: “He used to live with us.”

Professor Nick Potter [played

by Edward Everett Horton]: “We've come to warn his future bride about him—he

never puts the cap back on the toothpaste.”

Edward “Ned” Seton [played

by Lew Ayres]: “Mm-hmm. Then we'll drink a toast to Johnny—he needs it.”

[Fills champagne glasses]

Susan: “Needs it?”

Ned: “Oh. I'm wrong. He

doesn't need it. Johnny's doing all right.”

Linda: “What's on your

mind, Ned?”

Ned: “Nothing's on my mind.”

Linda: “What do you mean—‘Johnny's

doing all right’?”

Ned: “I mean he's doing All

Right. He's having a whirl. Julia's got his hair slicked down and Father's

seeing that he meets the important people.”

Nick: “My word—are

there important people downstairs?”

Linda: “Oh—frightfully

important—that's why I want to give a party up here.”

Nick: [Quoting an

imaginary society column] “'Miss Linda Seton—on New Year's Eve— entertained

a small group of Very Unimportant People.'”

[Lifting champagne glass]

Nick: “To our hostess.”

[They all drink to Linda]

Linda: [Chuckles]

“May I drink, too?”— Holiday

(1938), screenplay by Donald Ogden Stewart and Sidney Buchman, based on the

play by Philip Barry, directed by George Cukor

The Philadelphia Story, a

later Katharine Hepburn-Cary Grant rom-com, may be more famous, but Holiday has

its own charms—especially in this New Year’s Eve scene, with Lew Ayres, as the sodden

truth-teller Ned, almost stealing the picture from its stars.

Most of all, what I love about this film (and the original play, by the marvelous Irish-American playwright Philip Barry) is the

sobriety that keeps rising to the surface amid all the bubbly—the price and

glory of Linda and Grant’s Johnny as they resist convention.

In recent years, some commentators have seen Ned’s

flip but ultimately submissive descent into alcoholism as the retreat of a gay

son in the face of an overpowering father. I dismissed that, until I noticed

other lines of his that seemed to sink under the weight of family history and suppressed

sexual orientation:

“You see, Father wanted a large family so Mother

promptly had Linda, but Linda was a girl so Mother promptly had Julia, but

Julia was a girl and the whole thing seemed hopeless. Then, the following year

Mother had me, it was a boy and the fair name of Seaton would flourish….Drink

to Mother, Johnny—she tried to be a Seaton for a while, then gave up and died.”

In this same dynamic of a wisecracking drunk who

constantly disappoints his father, other movie fans may be reminded of Dudley

Moore’s decidedly heterosexual Arthur.

Aficionados of real estate development—not to mention

of Presidential history—will summon up a relationship more recent, crushing, and sad.

(While The Philadelphia Story was turned into a

celebrated Cole Porter musical, Holiday was transformed into one that

gained far less notice: Happy New Year. This 1980 Broadway production,

while also featuring songs by the great songwriter, also demonstrated the

importance of a musical “book”—or, in this case, with an awkward one

constructed by Burt Shevelove, what can happen with an inadequate one.)

Wednesday, December 30, 2020

Photo of the Day: ‘Rapture on the Lonely Shore’—Hilton Head, SC

There is a rapture on the lonely shore,

There is society where none intrudes,

By the deep Sea, and music in its roar:

I love not Man the less, but Nature more,

From these our interviews, in which I steal

From all I may be, or have been before,

To mingle with the Universe, and feel

What I can ne'er express, yet cannot all conceal.” — English Romantic poet George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812)

Lord Byron never visited America, let alone the shore of South Carolina. When I took this photo while on vacation in Hilton Head six years, the beach at that point in the day was not “lonely.” But I certainly felt the “rapture” he evoked in this passage as I pedaled my bike on the shoreline.

In these dying days of a year darkened by COVID-19, memory is the only way to experience vistas like this once taken for granted in the era of untrammeled travel. But memory—and the magical verses like these—remain, for all that, enormously powerful.

Let’s hope that, at some

point in the new year, we will have once again the opportunity “to mingle with

the Universe” without fear.

Quote of the Day (Victor Hugo, on the Learned Man)

“The learned man knows that he is ignorant.” — French novelist-poet Victor Hugo (1802-1885), Victor Hugo's Intellectual Autobiography (Postscriptum de Ma Vie), translated by Lorenzo O’Rourke (1907)

Tuesday, December 29, 2020

Quote of the Day (Dean Acheson, on Thinking That ‘The Human Mind Could Be Moved by Facts and Reason’)

“I was a frustrated schoolteacher, persisting against overwhelming evidence to the contrary in the belief that the human mind could be moved by facts and reason."—American Secretary of State and Pulitzer Prize-winning memoirist Dean Acheson (1893-1971), Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department (1969)

Monday, December 28, 2020

Quote of the Day (Andy Simmons, Imagining an Airbnb Review of the ‘Game of Thrones’ Red Keep)

“If you can get past the beheadings, poisonings, pillaging, and spotty Wi-Fi, then this is a fun place. I swear, after every battle, the wine flows and people make out. So much better than the Sandals Resort in Jamaica!” —Andy Simmons, “Here’s What Airbnb Reviews Would Look Like for Fictional Places,” Yahoo!Sports, May 23, 2018

Sunday, December 27, 2020

Spiritual Quote of the Day (Pope Francis, on Why Jesus Was ‘Born an Outcast’)

“The Son of God was born an outcast, in order to tell us that every outcast is a child of God.”—Pope Francis, Christmas Eve Mass 2020, quoted in Christopher Lamb, “Every Outcast is a Child of God, Says Pope,” The Tablet, Dec. 24, 2020

Saturday, December 26, 2020

This Day in Cold War History (‘Porgy and Bess’ Staged in Leningrad, at Soviet and US Turning Points)

Dec. 26, 1955—In the first American theater troupe appearance in the Soviet Union since the Bolshevik Revolution, the international touring company of Porgy and Bess performed in Leningrad.

The massive company, nearly 100 strong, presented the

1935 “folk opera” by George and Ira Gershwin amid simultaneous

watersheds in U.S. and Soviet history. In America, the civil-rights movement

was picking up momentum with the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education

of Topeka, Kansas decision and the onset of the Montgomery bus boycott. In

the U.S.S.R., Nikita Khrushchev, having been named secretary of the Communist

Party, was gauging how to expose Joseph Stalin’s totalitarian abuses.

In this atmosphere, the production by the Everyman

Opera Company became a vehicle for political controversy, as this work had been

since its Broadway premiere 20 years before. Then, it was a matter of domestic

dispute: How accurate was its depiction of African-American life? Now, many

wondered if the Soviets would use the show to highlight American racial inequality

as Marxism competed against the free-enterprise system in the postwar order.

So much intrigue and suspense surrounded the event

that it received unusually extensive press coverage, including by CBS

correspondent Daniel Schorr and Truman Capote, stepping away from

novels, musicals and film scripts to venture into creative nonfiction for The

New Yorker Magazine. Capote’s chronicle of the epic trip, The Muses Are Heard, became his first significant step into the genre that he

would transform with In Cold Blood.

The all-black cast (insisted on from its Broadway

premiere) of the Everyman group had already been touring for four years,

including a triumphant stop earlier that year before a demanding Italian

audience in Milan's La Scala to perform the theater's first American opera. But

the stakes were far higher when Everyman director and co-producer Robert Breen led his company into Russia.

Throughout the international tour, the group had been

sponsored by the U.S. State Department. But funding was denied for the Russian

leg of the long tour because the State Department felt the Soviets would use

this depiction of poverty in Charleston’s Catfish Row in its propaganda war

against America.

Instead, funding was handled by the Soviet Ministry of

Culture, and as the Everyman group prepared for the show, they anxiously

considered whether they were being watched by their hosts and how they should

answer incessant questions about the civil-rights struggle going on back at

home.

It is hard not to read Capote’s account

without admiration for the intelligence, talent and dignity of its

African-American cast, each member balancing fidelity to an imperfect country

that could easily be embarrassed on the world stage with their commitment to

truth and justice.

It is equally difficult to read Capote without rolling

one’s eyes at State Department representatives addressing the cast in carefully

calibrated terms, at other whites along for the ride (e.g., Ira Gershwin’s

wife Lenore on rumors that their hotel rooms would be wired: “Where are we

going to gossip? Unless we simply stand in the bathroom and keep flushing…”)

and at Capote’s trip through a local department store.

Despite some jitters before and during the performance

on how Soviet listeners were reacting (Bess’ adjustment of her garter upset

some local prudes), the show moved audiences in Leningrad and, later, Moscow. It

paved the way for later productions in Mother Russia of My Fair Lady, The

Threepenny Opera, Annie Get Your Gun, Kiss Me, Kate, and Sugar.

Quote of the Day (Margaret Millar, on Accepting Lies)

“It was better to feed him a lie he would swallow than a truth he would spit out.”—American mystery novelist Margaret Millar (1915-94), The Fiend (1964)

Friday, December 25, 2020

Song Lyric of the Day (Edmund Hamilton Sears and Richard Storrs Willis, on How ‘It Came Upon the Midnight Clear’)

That glorious song of old,

From angels bending near the earth,

To touch their harps of gold:

‘Peace on the earth, goodwill to men,

From heaven's all-gracious King.’

The world in solemn stillness lay,

To hear the angels sing.”—“It Came Upon the Midnight Clear,” lyrics by Unitarian minister-poet Edmund Hamilton Sears (1810-1876), music by American composer Richard Storrs Willis (1819-1900), from American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century, Vol. 1: Philip Freneau to Walt Whitman, edited by John Hollander (1993)

Edmund Hamilton Sears wrote these lyrics in 1849, at a point that many contemporary readers might appreciate: a time of public disruption and private depression. The United States was still coming to terms with the nature of its recent victory in the deeply polarizing Mexican War: the vexing question of whether to admit the newly won territory as free or slave states. At the same time, after a year off because of health issues, he was trying to resume his ministry, this time with a congregation in Wayland, Mass.

On her blog “History? Because It’s Here!” Kathy Warnes has a fine post giving more details on the life and career of Sears, as well as on how Willis and, over in the U.K., Arthur Sullivan wrote melodies to lyrics that hover between hope (the singing of the angels) and despair (“the woes of sin and strife”).

Incidentally, the image

accompanying this post is the 1500 painting The Mystical Nativity, by Sandro

Botticelli (ca. 1445-1501)—the only signed work by the Italian Renaissance

master.

Thursday, December 24, 2020

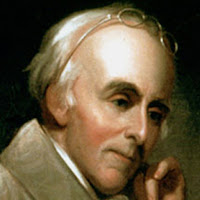

This Day in Medical History (Benjamin Rush, Reforming Doctor Who Signed Declaration of Independence, Born)

Dec. 24, 1745—Benjamin Rush, a doctor at the forefront of intellectual and reform movements in the first four decades of the American republic—including signing the Declaration of Independence—was born in Byberry Township, Penn. (The date used here was according to the Julian Calendar that prevailed in England and its colonies at the time.)

Last week, I wrote a post about another underrated Founding Father: John Jay. But, in its way, Rush’s career was more varied,

more interesting—and more tragic. After all, how many other figures are

considered so crucial to the origins of abolitionism, prison reform,

psychiatry, eugenics, and substance abuse treatment—or been forced to put many

of his concepts into practice by treating his own mentally ill son?

As a member of the Continental Congress whose

activities ranged across multiple fields, Rush may have been surpassed only by

two friends who also signed the Declaration, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas

Jefferson. He embodied the best notions of the American Enlightenment for his belief in republicanism, toleration, scientific progress, and the elevating impact of education.

Yet, though regarded as the most famous and brilliant American

physician of his time, his renown faded somewhat in the two centuries after his death

for three reasons: his relatively brief political career, a longtime lack of

access to his copious writings, and out-of-context misunderstandings about some

of the more controversial aspects of his medical career.

In recent years, Rush has become the focus of some

long-overdue scholarly attention. First, Stephen Fried’s highly acclaimed biography of the doctor appeared two years ago. Second, the current

COVID-19 pandemic has led scholars to re-examine Rush’s controversial role in a

major epidemic of his career: a Yellow Fever outbreak in Philadelphia.

Though not the sole physician who signed the

Declaration, Rush was the only one to receive a university education in

medicine (the College of Philadelphia, then the University of Edinburgh).

From his late 20s on, he became active in politics: persuading the recent English immigrant Thomas Paine to call his incendiary pro-revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense; discussing how to advance the new movement while dining at Philadelphia’s City Tavern with John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington; and, after signing the Declaration, leaving his pregnant wife behind to serve as physician in chief of the military hospital of the Middle Department of the Continental Army.

In the latter frenetic period, Rush was a trusted

confidante and admirer of Washington: witnessing him clutching a page saying

“Victory or death” (the watchword for the attack) before crossing the Delaware at the Battle of Trenton;

treating the dying Gen. Hugh Mercer at the Battle of Princeton; slipping out of

the clutches of the British after being briefly captured at the Battle of

Brandywine; and writing an essay on

improving soldiers’ medical care that Washington pressed on his

subordinates.

But before long, Rush would also display the habit of

caustic, impolitic and sometimes indiscreet writing that attracted a host of

enemies. He became appalled by medical treatment of soldiers at the hands of

his superior, John Shippen, then at the Continental Congress for clearing him

of wrongdoing.

Rush made an even more significant enemy when he

penned an anonymous letter to Patrick Henry that was critical of Washington. Henry disregarded Rush’s plea to burn the letter immediately,

instead passing it along to the general. Washington was so angry at Rush’s

duplicity that the doctor felt compelled to resign his post.

In the 1780s, students rather than soldiers became the

primary focus of Rush’s attention. At the University of Pennsylvania, he served in a number of capacities over the years, including professor of

chemistry, professor of the theory and practice of medicine, and professor of

the institutes of medicine and clinical practice. Unlike many of the other

Founding Fathers, Rush was egalitarian in outlook, believing that a good

education should be enough to qualify candidates for public office.

All the while he was lecturing to enthralled students (more than 3,000 in his 45-year career),

Rush was maintaining a vigorous publication schedule (an estimated 85 significant publications, including the first American chemistry textbook) and becoming what would

now be thought of as a public intellectual on health and educational matters:

* He founded Dickinson College in Carlisle,

Pennsylvania (1783), Franklin College (now Franklin and Marshall) at Lancaster (1787),

and the College of Physicians (also 1787);

* He sought, at Pennsylvania Hospital, the nation's first hospital, to get better

funding for the mentally ill, and to stop the shameful practice of warehousing

them;

* He called for treating addiction as a medical

problem years before this became standard practice;

* He sought to reconcile two modes of beliefs that he

heartily embraced: rationalism and religion;

* He proposed a national system of public education

with a federal university to train public servants; and

* He advocated for the education of women.

On top of all these efforts, Rush not only called for

an end to slavery but, differing from the conventional wisdom of the time,

declared that there was nothing physically different about African-Americans

that would prevent them from achieving as much as whites.

Unfortunately, Rush endangered his reputation for

being in the vanguard of progressive thought—not to mention his professional credibility—by his role in Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic of 1793. (A thorough but critical examination of his role is provided by Robert L. North's "Benjamin Rush, MD: Assassin or Beloved Healer?" in a 2000 article for the Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings.)

At the start of the epidemic, Rush’s standing with the

public actually rose, as he was one of the few physicians even to stay in the

city to treat patients. But no approach he tried with patients seemed to work.

At this point, recalling a 1744 medical paper, Rush

hit on the expedient of bloodletting and purging. Even when that didn’t work,

he only resorted to it all the more often. (Ironically, Rush had stumbled onto

they key to yellow fever outbreaks—his notes refer at one point to “Moschetoes”

that were “uncommonly numerous”—but he never made the connection to the

disease’s origin.)

William Safire’s novel Scandalmonger (2000)

takes the viewpoint of Rush’s enemies by depicting him as a "murderous

quack" and "Dr. Death," but it leaves out an important bit of

context: Nobody else at the time had the least idea of what caused the

disease. But the damage to the esteemed doctor’s credibility was done. He

felt compelled to withdraw from some of his positions, and even his practice

suffered for a time.

Adams’ appointment of his old friend as Treasurer of

the U.S. Mint enabled Rush to rebuild his reputation even as he re-entered public

service. He remained wed, fatally, to his old idea on fever—when stricken with

typhus in 1813, he instructed that he be treated through bloodletting and

purging—but at his death, a grateful populace turned out en masse to pay tribute to one

of Philadelphia’s most honored citizens.

In his 2018 biography, Rush: Revolution, Madness,

and Benjamin Rush, the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father,

Stephen Fried explained how the physician-patriot’s intimate connection to the

leading lights of his time led to his relative undervaluation by decades of historians.

At his death, descendants of several prominent families had reason not to have

his correspondence or journal entries cited by biographers--materials that would have confirmed his central in the American Revolution:

*Jefferson’s family did not want airing of his

skepticism about the divinity of Christ—opinions that could have been

misconstrued to suggest he was an atheist—or his request to the doctor for the

best way to treat his hemorrhoids;

*Adams’ descendants were sensitive about revealing

the President's anguish over a son’s descent into and death from

alcoholism—a pattern that repeated itself with one of the children of John Quincy

Adams; and

*Rush’s family was not keen about divulging

the reason behind his disrupted friendship with George Washington, now firmly

established as the Father of His Country.

Even as he struggled with the personal tragedy of his son John--a physician who, after killing a friend in a duel, became so mentally unstable he needed to be placed under his father's care-- Rush, in his last decade, performed one of his greatest services to posterity by relentlessly urging old friends Adams and Jefferson to repair the breach that had developed because of their competition for the Presidency.

That reconciliation not only helped heal old wounds between the

proud old patriots but led to one of the most extraordinary bursts of

correspondents among two ex-Presidents—creating a treasure trove that scholars

have used since to better understand the extraordinary generation that produced

such revolutionaries as Adams, Jefferson and mutual friend Rush.

Movie Quote of the Day (‘It’s a Wonderful Life,’ With George in Mr. Potter’s Spiderweb)

Mr. Potter [played by Lionel Barrymore] [to George Bailey]: “I'm offering you a three-year contract at $23,000 a year, starting today. Is it a deal or isn't it?”

George Bailey [played by James Stewart]: “Well, Mr. Potter, I... I... I know I ought to jump at the chance, but I... I just... I wonder if it would be possible for you to give me 24 hours to think it over?”

Potter: “Sure, sure, sure. You go on home and talk about it to your wife.”

George: “I'd like to do that.”

Potter: “In the meantime, I'll draw up the papers.”

George: “All right, sir.”

Potter [offering hand]: “Okay, George?”

George [taking his hand]: “Okay, Mr. Potter.”

[As they shake hands, George feels a physical revulsion. He drops his hand, then peers intently into Potter's face.]

George [vehemently]: “No... no... no... no, now wait a minute, here! I don't have to talk to anybody! I know right now, and the answer is no! NO! Doggone it!” [Getting madder all the time] “You sit around here and you spin your little webs and you think the whole world revolves around you and your money. Well, it doesn't, Mr. Potter! In the... in the whole vast configuration of things, I'd say you were nothing but a scurvy little spider!”—It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), screenplay by Frances Goodrich, Albert Hackett, and Frank Capra, based on an original story by Philip Van Doren Stern, directed by Frank Capra

I haven’t watched It’s a Wonderful Life yet this year, but after multiple viewings, I don’t think I need to anymore. Over the last few weeks, this snatch of dialogue sprang to mind.

I think many of us have encountered a “scurvy little spider” at some point in our lives. I can think of at least one at the national level—maybe you can, too.

The message of Frank Capra’s film classic—and of this holiday season—is that such ceaseless schemers don’t win, and that for every Potter, there’s a George Bailey in our community—and maybe even our own family.

Merry Christmas, Bedford Falls—and beyond!

(By the way, for an absorbing

look at one of the little-known aspects about the environment in which It’s

a Wonderful Life was released, see this article from the Website “History

Collection” about how the FBI initially regarded the film as Communist propaganda, even though Capra, a conservative Republican, not only loathed

Marxism but even Franklin Roosevelt. It seems that, in J. Edgar Hoover’s

paranoid organization, Mr. Potter was seen as an insidious reflection of the

capitalist system as a banker—even though George and Peter Bailey also ran financial

institutions.)

Wednesday, December 23, 2020

Photo of the Day: Brooklyn Campus Library, Pratt Institute, NY

While pursuing my master’s degree in library science at Pratt Institute, I spent many hours inside this landmark 1896 building constructed in the Renaissance Revival style. It is as beautiful outside, with its striking red bricks, as inside, with materials from the Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company.

Quote of the Day (William Seward, on ‘Intelligent Votes’ Needed to ‘Save the Great Democratic Government of Ours’)

No matter how the next few weeks will play out, the

convulsions since Election Day—at this point, sure to extend into

January—should refute the notion that voting doesn’t count.

Tuesday, December 22, 2020

Quote of the Day (George Eliot, on Why ‘Our Dead Are Never Dead to Us Until We Have Forgotten Them’)

“Our dead are never dead to us until we have forgotten them: they can be injured by us, they can be wounded; they know all our penitence, all our aching sense that their place is empty, all the kisses we bestow on the smallest relic of their presence.” —English novelist, translator, editor, and religious writer Mary Ann Evans, a.k.a. George Eliot (1819-1880), Adam Bede (1859)

Almost nothing was conventional about George Eliot:

her appearance; her religious skepticism; her piercing intellect at a time when

educating women was not a family priority; her longtime common-law marriage to editor

George Henry Elwes; her use of a male pen name so her initial novels would be

taken more seriously; and finally, her death at age 61 on this day 140 years

ago, in Chelsea, England, only six months after marrying a man 20 years her

junior.

She blazed her own path in literature as well, with

seven novels characterized by flinty realism and high moral seriousness. In

this year of COVID-19, when so many people all over the world have experienced

the death of family members or dear friends, the quote above seems not only a

fair sample of her attitude, but also an appropriate response to the sense of

loss so many feel.

Over the years, Eliot’s detractors (e.g., Mark Twain) have correctly noted her humorlessness, adding even heavier weight to her earnestness.

But Virginia Woolf, in a 1919 Times Literary Supplement essay on

the novelist’s career, generously but judiciously summarized her achievement by

noting that she “taken to heart certain lessons learnt early, if learnt at all,

among which, perhaps, the most branded upon her was the melancholy virtue of

tolerance; her sympathies are with the everyday lot, and play most happily in

dwelling upon the homespun of ordinary joys and sorrows.”

More pointedly, Woolf observed that in the 1871

masterpiece Middlemarch, Eliot had created, “with all its imperfections…one

of the few English novels written for grown-up people.”

(In an especially relevant post for our time, Delia da

Sousa Correa of London’s Open University has written for the Institute of

English Studies blog about the role of an earlier epidemic—a cholera outbreak in Britain—in Middlemarch.)

Monday, December 21, 2020

Photo of the Day: Dogs, Snow, and Sunset, on the First Day of Winter

I took the attached photo late this afternoon while in Overpeck County Park, not far from where I live in Bergen County, NJ.

Though I have taken many pictures in this park over the

years, the number of these snapped in winter is relatively small. And until

today, I had never seen anyone coming off the field in this park carrying skis.

(The field is completely flat, so the skier is, shall we say, highly unlikely

to pick up speed or face any sharp turns.)

Joke of the Day (Comic Steven Wright, on Why He Needs His Own Baby Monitor)

“I need one of those baby monitors from my subconscious to my consciousness so I can know what the hell I'm really thinking about.” — Stand-up comic Steven Wright quoted in Peter Keepnews, “A Strange Career Takes an Odd Turn,” The New York Times, Feb. 10, 2008

Sunday, December 20, 2020

Flashback, December 1945: ‘They Were Expendable,’ Ford Tribute to Naval Courage, Premieres

Navy personnel also helped create the film, including

screenwriter Frank Wead, a retired WWI pilot; director John Ford, a

captain in the Navy Photographic Field Unit; and one of the two male leads, Robert Montgomery, a real-life PT skipper in the recently concluded war.

One key cast and crew member, however, was not involved

in the war: the second male lead, John Wayne, who nevertheless used

the movie to recast his image successfully as a towering American hero.

Ford and Wayne made 20 films over 35 years, but in

certain ways this may have been the most pivotal. It certainly was the one that

tested the most the boundaries of their working relationship and friendship.

Ford, who had enlisted in the Navy even before Pearl

Harbor, had spent much of the prior four years in a documentary crew filming

battles, including Midway (where he continued shooting even after being

wounded, earning a Purple Heart for his gallantry). Throughout that time, he

had been after Wayne to “get into” the fight.

But Wayne—34 and able-bodied at the outbreak of

hostilities at Pearl Harbor—kept finding one reason after another not to join

up. He had suffered an injury during college that continually hampered his

function (though it hadn’t bothered him much while performing his own stunts

several years before). He was the sole support of his family (though that

status would change, as he was about to enter divorce proceedings). He couldn’t

get out of a contract with Republic Pictures without triggering a lawsuit (though

he didn’t test to see whether Republic head Herbert J. Yates was bluffing). He wrote

Ford about joining his photographic unit but kept postponing joining until after

his next picture.

In the end, Wayne was exempted from service due to his

age and family status. That didn’t sit well with, for instance, Pacific Theater

vets who, upon encountering Wayne on a USO tour, booed him raucously (an

incident recalled in William Manchester’s WWII memoir, Goodbye, Darkness).

While not a draft dodger, Wayne had not pressed his case

as vigorously as other stars had done. That rankled Ford, who before long was ridiculing

him repeatedly in front of the entire crew.

The baiting was in keeping with the longtime on-set behavior of Ford, an alcoholic bully who would often pick one person on each film to abuse. The director had, in prior movies, taken Wayne to task for, among other things, “walking like a pansy.”

Now, almost as soon as shooting

began on Ford’s birthday in February—with co-star Montgomery serving inadvertently

as a model of doing one’s military duty—Wayne found himself subjected to abuse

on a subject that would haunt him for the rest of his life: the not-so-subtle imputation that he was a "shirker."

Ford may have reached his zenith in sadism when he

asked why Wayne couldn’t even salute properly. Watching his co-star reduced to

what another actor in the production called “a quivering pulp,” Montgomery had

had enough. If Ford was subjecting Wayne to this treatment on his behalf, the

director should stop the treatment right now, Montgomery said.

Ford eased up—but only on this movie. More than a

decade and a half later, while shooting The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,

Ford asked James Stewart, a decorated pilot, what he had done in the war. Then

he turned to Wayne to ask what he had done.

One has to ask why Wayne continued to endure this

abuse—particularly by the early 1960s, the time of production on Liberty Valance,

when he was a box-office institution. Gratitude to Ford for rescuing him from “B”

Westerns with Stagecoach can only account for some of his forbearance.

True, there was also the possibility that Ford would offer

Wayne the chance to play increasingly psychologically complex variations on the

ideal of American manhood. But I think something else was involved, the same dynamic behind Montgomery’s work on this movie: the chance to learn from a

master of movie-making.

By the mid-1940s, Montgomery—more famous these days, as

I indicated in a prior post, as the father of Bewitched’s

Elizabeth Montgomery—was a highly regarded actor with his eye now trained on

behind-the-camera work. A year later, he would finally have the chance to

direct his first film, an unusual adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s detective

novel The Lady in the Lake.

But as he was playing the lead in They Were

Expendable, Lt. John Brickley (based on the real-life war hero Lt. John Bulkeley),

the actor—a bit nervous about not being in front of the camera for three years

during the war—was thinking about the next turn in his career. He didn’t

protest when Ford, after filming a scene according to his suggestion, then told

him to take the reel home with him, as they wouldn’t be using it.

Weeks later, after Ford suffered an injury while on location

in Florida, he had Montgomery film action sequences while he was recuperating. In

what must have thrilled the actor, Ford later claimed that he couldn’t tell the

differences between these scenes and those he had filmed.

As for Wayne: Playing Brickley’s second-in-command,

Lieutenant "Rusty" Ryan, was not only a chance for a high-profile

role in something besides a western, or even for making sizable elements

of the public forget his less-than-glorious part in the war, but also an

opportunity to learn lessons in directing from the universally acknowledged

master of the art.

By this time, a project of his own was germinating in

Wayne’s mind: making a film about the Alamo. Over the next 15 years, he would

hire researchers and put much of his own money behind this account of the legendary

last-ditch stand against Santa Ana. Even now, he was absorbing by osmosis how to

frame shots and other aspects of film.

The Alamo

was similar to They Were Expendable as a study of sacrifice in the face

of overwhelming odds. But, if film could be likened to song, Wayne had learned

the words but not the music that would make the experience indelible.

Over the course of his long career, Ford assembled a

de facto stock company of actors who, for better or worse,

were willing to endure his on-set dictatorship. He knew their talents and fit roles to them, and had learned to work even more smoothly with screenwriters such as Wead

and Frank Nugent (a former movie critic who would write the script for The

Searchers and other classic Ford westerns).

Wayne could not count on the same assets in making The

Alamo. He could not secure actors he had hoped for principal roles (Clark

Gable, Charlton Heston), so he had to hope that the ones he did secure (Richard

Widmark, Laurence Harvey) would mesh well with each other under his direction—a

hope unfulfilled in the final product.

More fatally, for all his interest in recreating the

Alamo with almost documentary exactness, Wayne lacked Ford’s intense

psychological identification with his material. From Midway to D-Day, Ford had

not just filmed men under fire but also, as one himself shooting amid the roar of battle, he had imbibed

their attitude toward war as a matter of stoic grace under pressure rather

than an exercise in jingoism.

Some of the best moments in They Were Expendable are

of men suddenly facing awesome odds with silent, grim but certain resolution:

being told, one by one, at a social gathering that Pearl Harbor has been attacked,

or, through a fluke of fate, losing one’s place on the plane taking select sailors

to the comparative safety of Australia. The Alamo exhibits none of this fatalistic attitude. It is more committed to waving the flag than in honoring the qualities that led men to carry it in the face of death.

The result: while They Were Expendable did not

lure a war-weary public to the box office, it has increasingly won critical

acclaim as one of the best WWII movies, while The Alamo is a long epic

that, for all its admirable intentions, lacks the psychological insight, pacing

or extraction of actors' best talents so characteristic of Ford

classics.

Spiritual Quote of the Day (St. Robert Southwell, on ‘The Burning Babe’ of Christmas)

Love is the fire, and sighs the smoke, the ashes shame and scorns;

The fuel Justice layeth on, and Mercy blows the coals,

The metal in this furnace wrought are men’s defiled souls,

For which, as now on fire I am to work them to their good,

So will I melt into a bath to wash them in my blood.’

With this he vanish’d out of sight and swiftly shrunk away,

And straight I called unto mind that it was Christmas day.”—English Jesuit, poet and martyr St. Robert Southwell (1561–1595), “The Burning Babe,” in St. Peter’s Complaint (1595)

Saturday, December 19, 2020

Photo of the Day: Flashback, November 2015, New Jersey State Botanical Garden, Ringwood NJ

I was stunned by the beauty of the New Jersey State Botanical Garden when I visited five years ago. This photo, I think, gives you a good idea of why I came to feel that way.

Quote of the Day (John Updike, on Exiting a High School to the Snowstorm Outside)

“What a crowd! What a crowd of tiny flakes sputters downward in the sallow realm of the light above the entrance door! Atoms and atoms and atoms and atoms. A furry inch already carpets the steps. The cars on the pike travel slower, windshield wipers flapping, headlight beams nipped and spangled in the ceaseless flurry. The snow seems only to exist where light strikes it.”— American man of letters John Updike (1932-2009), The Centaur: A Novel (1962)

Snow was common in the rural Pennsylvania area where John Updike grew up and where his early novel is set. I can still recall times seeing snowflakes as I stepped out of the gym of my high school in northern New Jersey in the 1970s.

But over the last few

years, it has become a rather unusual sight. Earlier this week, TV

meteorologists were telling us that there were only five inches of snow for

the entire winter last year in Central Park.

The snowstorm that blew through late Wednesday into

Thursday, the biggest in this area of the Northeast in the last five years, has more than made up for that total already. Updike’s description hints at the

danger in such a dangerous storm, but it is overwhelmed by the lyricism of this

passage.

In the same way, it is lovely to look out at snow, and

even more so to write about it—but, at a certain age in life (which I’m afraid

I have reached), not so much to be in the midst of it—steering one’s car if one

needs to drive, shoveling as bitter winds blow about you, shoveling again when

city plows push the snow back into the driveway and sidewalk you’ve struggled

to clear, and walking gingerly on streets that have iced up overnight.

Friday, December 18, 2020

Photo of the Day: Flashback, Spring 2016, Dahnert's Lake County Park, Garfield NJ

Some years ago, a local DJ, who roundly despised football, would play baseball music as a bit of counterprogramming on Super Bowl Sunday. In a somewhat similar spirit, as the dead icy hand (not to mention snowflakes) of winter falls on us, I thought I would give readers something to look forward to: spring, in the form of a photo I took in mid-April four years ago of Dahnert’s Lake County Park, at the western edge of Bergen County NJ.

Maybe by then, we will have something else to anticipate:

the gradual recession of the coronavirus that has had us in its grip since March,

blighting everyone’s lives in ways small and, unfortunately, large.

Movie Quote of the Day (‘Scrooged,’ on Christmas Programs’ Need for ‘Pet Appeal’)

Network president Preston Rhinelander [played by Robert Mitchum]: “Frank, have you any idea how many cats there are in this country?”

Frank Cross

[played by Bill Murray]: “No, I don't have those... no.”

Preston: “Twenty-seven

million. Do you know how many dogs?”

Frank: “In America?”

Preston: “Forty-eight

million. We spend four billion dollars on pet food alone. Now I have here a

study from Hampstead University which shows us that cats and dogs are beginning

to watch television. Now if these scientists are right, we should start

programming right now. Within twenty years they could become steady viewers.”

Frank [trying

to hide his incredulity]: “Programming? For cats?”

Preston: “Walk with me,

Frank.”

Frank [Whispering to

his secretary, Grace, as they leave the office]: “Call the police!”

Preston: “Now I'm not

saying build a whole show around animals. All I'm suggesting is that we

occasionally throw in a little pet appeal. Some birds, a squirrel...”

Frank: “Mice.”

Preston: “...mice!

Exactly. You remember Kojak and the lollipops? What about a cop that dangles

string as his gimmick? Lots of quick random actions. Frank, wasn't there a

doormouse in Scrooge?”

Frank: “No, but now

that you say it... I always felt that it needed a doormouse.”

Preston: “Doormice.

Better.”

Frank: “Bingo.”— Scrooged

(1988), screenplay by Mitch Glazer and Michael O'Donoghue, directed by

Richard Donner

Many years ago, when I rented this holiday flick on

video, its jokes fell flat for me. Maybe I’ve grown more cynical with age, but

when I watched this update on A Christmas Carol again on cable TV this

week, I thought that it lost its energy about halfway through, but it hit its

satirical targets far more often at the beginning.

This scene especially scored. (I have no idea how

Mitchum and Murray managed to keep straight faces as they filmed this.) In

fact, I think even more people can relate to it now. (While revenues for pet

services—i.e., visits to the vet—have been challenged during the pandemic, pet

food sales have continued to hold on, at least till recently—especially online

pet sales.)