Bring Virtue, Honor, Truth, and Loyalty,—

Bring Faith that sees with undissembling eyes,—

Bring all large Loves and heavenly Charities,—

Till man seem less a riddle unto man

And fair Utopia less Utopian.”—Southern poet, musician, literary critic, and academic Sidney Lanier (1842-1881), “Ode to the Johns Hopkins University (Read on the Fourth Commemoration Day, February 1880),” in Poems of Sidney Lanier (1885)

I found these lines while tracking down the source of a quotation from Helen Keller’s The Story of My Life: specifically, that phrase “large Loves and heavenly Charities.” That led me to this poem and Sidney Lanier, who preached here a message of idealism and charity—and who was himself a casualty of a society that had lost that capacity.

Like Robert Louis Stevenson, Lanier ended up disregarding his father’s wish that he practice the law and took up poetry—which, along with his skill in playing the violin, flute, piano, banjo and guitar, evidenced his inclination towards the arts.

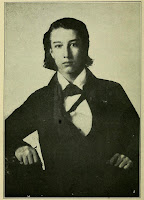

Most photos of Lanier show him bearded, in his later years. I prefer this one, from age 15, where you can see him in all his youthful promise.

But the poet-musician’s life was transformed—and, eventually, curtailed—by the Civil War. Leaving an offer as a tutor at Georgia’s Oglethorpe College, he joined the Confederate Army. In 1864, after transferring to a blockade runner seized by the Union, he was imprisoned and contracted tuberculosis—the disease that killed him at age 39.

I first came across Lanier’s name in a high school English anthology from the late 1960s. Even then, he was considered old-fashioned for exhibiting the influence of Anglo-Saxon and Romantic poets.

“In Lanier,” Edmund Wilson wrote in his influential 1962 overview of the literature generated by the Civil War, Patriotic Gore, “the chivalric romance of the South was to merge with German romanticism and to become inflated and irised, made to drip with the dews of idealism.”

Critical disdain only gathered force in the years afterward because Lanier’s style, unlike Walt Whitman’s or Emily Dickinson’s, was not original for his time; he was crowded out of “best of” poetry collections by 20th-century giants like the “beat” and “confessional” poets; and some of his verses, written in African-American dialect, are dated.

Though not a slave trader or slave owner himself, or even a veteran of combat (according to this 2020 Montgomery Independent article, he only led his unit’s band and never fired a shot), Lanier, like many white male southerners of his time, served in the Confederacy’s armed forces and in the Reconstruction Era wrote verses critical of civil rights for freedmen. That put him in the crosshairs of the movement to rename southern schools to remove vestiges of the slavery and Jim Crow eras.

After some heated debate, the Austin (TX) school named in Lanier’s honor was changed in 2019 to commemorate Juan Navarro, a 2007 graduate who died in Afghanistan five years later from an explosive device.

In reading about Lanier’s life and character, I couldn’t

help but think of Gone With the Wind’s Ashley Wilkes—another bookish,

sensitive scion of the Old South who, out of loyalty to his state, marched off

to a war that ends with his life “permanently shattered once the North wins the

war,” as Marc Eliot Stein (aka Levi Asher) noted in this 2015 post from his blog “Literary Kicks.”

Stein’s characterization of Wilkes’ genteel racism, born

of a “fear of invasion” (in this case, Northerners out to destroy slavery and,

with it, the antebellum plantocracy), applies just as readily to Lanier—who, in

one of the first examples of what might be termed “Lost Cause literature,” memorialized

one of the fallen heroes of the defeated South in “The Dying Words of Stonewall Jackson.”

It was deeply tragic that a multi-talented artist and

intellectual like Lanier had his life cut short before he could achieve even

more. It was also tragic that he could never see beyond the closed circle of

his society and imagine a life of opportunity for freedmen.

These days, for the first time in my lifetime, the American

political atmosphere has been inflamed by talk of civil war. We would do well to

follow the high ideals that Lanier advocated in the verses I quoted above, rather

than commit to the lack of a broader vision that wrecked his world and his

life.

No comments:

Post a Comment