“A primary complaint here [Hollywood] is overpopulation; old-guard natives tell me the terrain is bulging with ‘undesirable’ elements, hordes of ex-soldiers, workers who moved here during the war, and those spiritual Okies, the young and footloose; yet walking around I sometimes have the feeling of one who awakened some eerie morning into a hushed, deserted world where overnight, like sailors aboard the Marie Celeste, all souls had disappeared. There is an air of Sunday vacancy; here where no one walks cars glide in a constant shiny silent stream, my shadow, moving down the stark white street, is like the one living element of a Chirico. It is not the comfortable silence felt in small American towns, though the physical atmosphere of stoops and yards and hedges is very often the same; the difference is that in real small towns you can be pretty sure what sorts of people there are hiding beyond those numbered doors, but here, where all seems transient, ephemeral, there is no general pattern to the population, and nothing is intended—this street, that house, mushrooms of accident, and a crack in the wall, which might somewhere else have charm, only strikes an ugly note prophesying doom.” —American fiction writer and essayist Truman Capote (1924-1984), “Hollywood” (1947), republished in Portraits and Observations: The Essays of Truman Capote (2007)

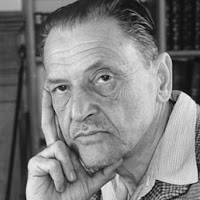

The pursuit of fame can bring the unwary to a desolate

place—a lesson that Truman Capote, born 100 years ago today in New Orleans,

learned firsthand but, to his loss and literature’s, managed to forget.

When I considered my choices for a post commemorating Capote’s

centennial, I thought of either a quote from his own work, giving a taste of

his impeccable writing style, or one from someone else about the author of In

Cold Blood. Rather than choose one to the exclusion of the other, I decided

to take both.

The paragraph opening this post is an example of the

first option; the following, from an April 1988 Esquire essay by

his Hamptons neighbor, A Separate Peace novelist John Knowles, of the

second:

“Truman Capote really was alone, and he knew it. No

one anywhere on earth can have looked like him, with his odd Pekingese

features, or above all sounded like him when he spoke. This very short,

thick-legged person with his big head and yellow, later gray bangs, speaking in

a tissue-paper thin, whiny lisp, was not at all like anybody else. Clothes were

not manufactured that fit him; no voice anywhere echoed his. When he would

merely enter a room or utter a few words, strangers stopped short, jerked their

heads around to behold him, usually—until he became so famous—with at least a

tinge of mockery, or hostility.”

Few writers have so adeptly captured Capote’s oddness,

vulnerability, and sense of remove better than Knowles—or how, “as a form of

self-protection, Truman made himself the only writer in the world after Ernest

Hemingway whom the man in the street recognized on sight.”

The name of the other author that Knowles drops in

that sentence is a signal of what’s to come: a writer who, believing he wears “the

invisible, protective shield of celebrity,” instead falls victim to his

self-created legend.

By the mid-1960s, it was hard to miss Capote and his work,

with adaptations not only of In Cold Blood but also Breakfast at

Tiffany’s, and, for television, A Christmas Memory and The

Thanksgiving Visitor. And, of course, there was the masked “Black and White

Ball” that Capote ostensibly threw for Washington Post publisher Katharine

Graham, but which also, not so coincidentally, raised his own profile.

A decade later, something was amiss. Most observers

trace Capote’s decline to his disastrous publication of the “La Côte Basque

1965” chapter of his projected roman a clef, Answered Prayers.

But the ostracism that Capote suffered at the hands of

the high-society “swans” he betrayed only accelerated deterioration that had

set in already, in much the same way that two plane crashes only a day apart that

Hemingway survived in 1954 marked the point of no return for a creative and

psychological degeneration previously in motion.

There were distractions aplenty that Capote didn’t need in the Seventies:

*a 1978 appearance on the egregious Gong Show imitation, The Cheap Show;

*his feature-film debut as an

actor, Murder by Death, which was so disastrous that screenwriter spent

virtually the entire production unsuccessfully pressing to have him replaced by

"any actual member of the Screen Actors Guild";

*his frequent presence as a guest on The Tonight Show; and

*a 1978 interview with Stanley Siegel that turned so rambling, incoherent and disastrous that the morning talk-show host asked on the air if the author was "feeling all right."

As with Hemingway, while the discipline of sitting

down at a typewriter remained intact for Capote, an essential creative skill

had been dulled by the years of substance abuse: the creative faculty that

would enable him to detect and fix what was wrong with a day’s work and push it

to completion.

Nearly four decades after Capote journeyed to

Hollywood, he met his end there in the home of one of its denizens: one of the

few female friends not to desert him in the wake of Answered Prayers,

Johnny Carson’s ex-wife Joanne.

For most of his career, Capote’s work was a model for how

to write. His death was a model for how to squander a writer’s capacity.

Or, as Knowles concluded in his poignant reminiscence:

“The autopsy found the failure of various organs, but I knew that he had died

because he had used up all of the things he had ever lived for.”

.jpg)

.jpg)