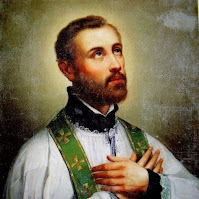

Apr. 7, 1541—On his 35th birthday, Francis Xavier departed Lisbon, Portugal with two Jesuit colleagues for Goa, India—on what would begin 11 years of missionary work halfway around the world, with the Spanish native never returning home.

I’ve come to think of Xavier as the St. Paul of the

Far East. In fact, in certain ways, his adventures and achievements may surpass

those of the Apostle to the Gentiles. Xavier never wrote texts that defined the

nature of Christianity, or even, like mentor Ignatius Loyola, guidelines

for what became a global religious order.

But Paul, for all his hardships (shipwreck,

imprisonment, martyrdom), journeyed in lands largely under an established order

that he knew well: the Roman Empire. Xavier went to lands that had only

recently been opened to European traders—or worse yet, lands that feared and

retaliated against Westerners.

Xavier could never have undertaken an activity with

such uncertainty and risk had he not mentally prepared himself on multiple fronts. A

brilliant scholar at the University of Paris, he had challenged his fellow

Basque and roommate Loyola on theological matters before his

skepticism melted at last, joining him and six others in 1534 in taking vows as

the first members of the Society of Jesus.

Although he had to resolve his intellectual doubts before joining what came to be known as the Jesuits, a far more intense trial awaited Xavier in the first year following his ordination, when he arrived in Venice to serve in a hospital for incurable patients. The charisma that drew others to him at the university was not enough here.

Now, he had to develop an

all-encompassing zeal for serving others that would help him surmount an instinctive

revulsion at the stench and ugliness of the hospital, all while maintaining

faith that God would see him and those to whom he ministered through their

trials.

All the toughness he had learned could only go so far

in preparing Xavier after he answered a request by King John III of Portugal to

evangelize the East Indies. The voyage, entailing rounding the Cape of Good

Hope, lasted 13 months, in an era when a ship’s inhabitants could fall victim

as easily to scurvy and dysentery as to pirates. The destination, Goa, provided

scant comfort—a slave port marked by the physical abasement of the conquered

and the moral debasement of the conquerors.

But Xavier never forgot his objective. As he wrote

once he reached India: “I looked or desired for nothing here but to wear myself

out with work and sacrifice my life itself in bringing about the salvation of

souls.”

His first task was one he was familiar with from Venice: ministering to the sick in hospitals. He began to make his mark outside after several months by walking the streets of Goa, ringing a bell that attracted children whom he would then catechize. Later, he turned his attention to the pearl fishermen on the eastern coast of Cape Comorin, using basic Christian prayers translated into Tamil. Over three years he traveled tirelessly, even reaching as far as Ceylon.

Frustrated by the obstacles represented by Portuguese political and military officials, he struck out for Malacca in 1545, then for the Molucca Islands. All the while he had to deal with work just as necessary but sometimes not as pleasing as preaching: supervising the men inspired by his example who were now flocking to missionary work from Ormuz to Indonesia—an activity that could mean recruiting native converts into the priesthood, but could also mean reproving or even removing Europeans he did not believe measured up to the tasks ahead of them.

While bringing Christianity to the Far East—or rekindling it among faithful not ministered to in years—Xavier was also lighting the way for future missionaries through his letters back home. Though modern readers may read this vast correspondence from an anthropological point of view—as a record of how a Westerner reacted to the customs and living conditions of exotic people—his contemporaries took spiritual sustenance from his reflections on how he survived adverse conditions:

“The day we encountered these disasters and all that night, God our Lord was pleased to grant me the great grace of wishing to make me feel and know through experience many things with respect to the cruel and dreadful fears which the enemy causes when God permits him (…) The best of the remedies at such times is to show very great courage against the enemy, having no trust whatever in oneself but great confidence in God.”

In 1549, with a couple of Japanese converts, Xavier

took up the last great missionary work of his life: evangelizing Japan—first by

taking a year to learn the language and customs, then another two in

evangelizing and setting up communities that would carry on his work afterward.

In 1552, he turned his attention to China. He was on the Island of Sancian off

the coast of that country when he fell ill and died in December 1552.

Within weeks of his death, astounding accounts—including

the incorruptibility of his body after his passing and miracles attributed to

him—began to circulate. In 1622, he was canonized along with his beloved mentor

Loyola. Credited with as many as 30,000 converts in his lifetime, he richly

earned his posthumous distinction as the patron saint of Catholic missionaries.

No comments:

Post a Comment