“The minister of propaganda, overlord of the spiritual life of millions, limped nimbly through the glittering throng which bowed down before him. An icy wind seemed to blow as he passed. It was as though an evil, solitary and cruel god had clambered down among the everyday bustle of pleasure seeking, cowardly, pitiful mortals. For several seconds the whole company remained as if paralyzed with horror….Hate and humility shone in the timid gazes turned on the fearsome dwarf. The object of attention tried an affable smile, which stretched his thin-lipped mouth from ear to ear, to soften the dreadful spell he cast about him. With a friendly expression in his sly, deep-set eyes, he was at pains to charm and placate. Dragging his clubfoot gracefully behind him, he moved agilely through the room, showing these two thousand slaves, fellow-travelers, swindlers, dupes and fools the profile of a bird of prey. All the while his eyes bore a malicious, abstracted smile as they flitted over the group of millionaires, ambassadors, regimental commanders and film stars. It was when he came to the director of the state theater, Hendrik Hofgen, privy councillor and senator, that his glance at last came to rest.”—German novelist Klaus Mann (1906-1949), Mephisto, translated by Robin Smyth (original publication, 1936; English translation, 1977)

When I was considering a literary work that conveyed

an essential quality associated with Halloween, I thought of how the horror genre in fiction and film often acted as a metaphor for the terror of everyday life.

Then I imagined instances of how actual historic terror needed little artifice. Nothing to my mind surpasses the rise of Nazism and the

monstrous evil it unleashed on the world.

The Faust legend of bartering one’s soul to the Devil, which originated with an actual historical German

alchemist of the Renaissance, has long fascinated intellectuals and entertainers in the land in which he was

born, but few figures as much as Nobel Literature laureate Thomas Mann and his

son Klaus. Both made their Faust stand-in a member of the German culturati: the

fictional composer Adrian Leverkühn in Thomas' four-decade saga Doktor Faustus,

the actor-turned-theater director Hendrik Hofgen in Klaus’ Mephisto.

Despite choosing the same legend as the source of

their work, Thomas and Klaus treated their subjects quite differently. Doktor

Faustus is oblique, even elliptical in tying the fate of its protagonist to

that of the Third Reich as a whole. In contrast, as seen here, Mephisto

is a searing satire of intellectuals exchanging what are ostensibly supposed to

be their greatest ideals for personal advancement.

In the opening chapter from which the above quote comes, Klaus Mann gives no names to the members of the Nazi hierarchy, but he identifies them by title and physical appearance so exactly that nomenclature is unnecessary.

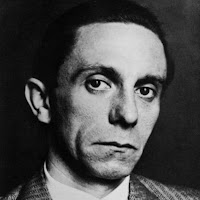

That’s particularly the case with minister of

propaganda Joseph Goebbels—rendered here in all his physical and

moral deformity, in a fashion perhaps only surpassed by King Richard III as

dramatized by William Shakespeare.

The figure approached by Goebbels at the end of this

quote—making his stage entrance, as it were—is Hendrik Hofgen. The

actor-director, about to be complimented by both Goebbels and the propaganda

chief’s rival in Adolf Hitler’s circle, Herman Goering, has achieved a career

zenith with his production of Goethe’s Faust, in which he has played Mephistopheles,

the wily devil who lures Faust into surrendering his soul.

That production will become a defining one, as Hofgen

bargains away what he cares for the most—his art—in an attempt to ally with the

evil regime stalking his nation.

If the portrait of Hofgen becomes so lacerating, it is partly because Mann knew his subject at close range. The real-life inspiration for Hofgen, Gustaf Gründgens, was in fact Mann’s onetime brother-in-law and fellow sympathizer with the left, but had long since yielded both the family connection and his politics.

Klaus shared the opinion of his sister Erika that

Grundgens’ Weimar-era leftism was “insincere, snobby, and quasi-opportunistic.”

“Opportunistic”—maybe one of the best adjectives one

can come up with to describe how the monsters marauding geopolitics came to

establish their shadowy dominion. A monster does not rise unaided, but instead

with what Klaus Mann aptly summarized as “slaves, fellow-travelers, swindlers,

dupes and fools.”

Hitler may have used Goebbels to spread hatred and

untruths through radio, movies and theater, just as Donald Trump has employed

Steve Bannon to broadcast “alternative facts” through social media. But

propaganda mavens need their own henchmen. Bannon has found his among GOP

lawmakers on Capitol Hill too terrified of their once and future Presidential

standard-bearer.

In the 1930s, Germany—the land that had given the world Martin Luther, the author of The Freedom of a Christian—found itself under the sway of Goebbels, “overlord of the spiritual life of millions.” Those intellectuals and entertainers who, unlike the Mann family, did not go into exile soon learned to look the other way, then bend, smile and fawn over the thugs now running their country.

The “dreadful spell” cast by Goebbels and his minions

continues to be felt by the all too susceptible members of our world,

three-quarters of a century after the fall of the prematurely named “Thousand-Year

Reich.”

.jpg)