“It was one of those midsummer Sundays when everyone

sits around saying, ‘I drank too much last night.’ You might have heard

it whispered by the parishioners leaving church, heard it from the lips of the

priest himself, struggling with his cassock in the vestiarium, heard it

from the golf links and the tennis courts, heard it from the wildlife preserve

where the leader of the Audubon group was suffering from a terrible hangover. ‘I

drank too much,’ said Donald Westerhazy. ‘We all drank too much,’

said Lucinda Merrill. ‘It must have been the wine,’ said Helen Westerhazy. ‘I drank

too much of that claret.’” —Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist and

short-story writer John Cheever (1912-1982), “The Swimmer,” originally printed

in The New Yorker, July 18, 1964, reprinted in The Stories of John Cheever (1978)

In the middle of yet another ungodly heat wave, there’s

nothing like a nice, cool swim.

Well, even a good idea can be carried a little too

far sometimes. Just how far—and how wrong—that kind of idea can be was conjured

up by one of the great chroniclers of postwar suburbia.

A full immersion in the waters of John Cheever

is enough to get you drunk by osmosis, and one of his most anthologized short

stories, “The Swimmer,” wastes no time doing so, in this first paragraph.

Even on Sunday, a day not just of liturgical but

recreational grace, inebriation cuts across vast cross-sections of the New York

suburb in which this tale is set. Not only is the phrase “drank too much” used

four times in the quoted paragraph above, but “drank” is italicized in each

case.

Even before the title character is introduced, the

major cause of his ultimate degeneration has been identified, albeit as a

characteristic shared with the friends and ex-friends increasingly nettled by

his presence.

“Drunk” is not the only word repeatedly employed

throughout the story. So are “seemed” and “might,” with each use attached to an

associated image indicating that the perceptions of the protagonist, Neddy

Merrill, will be fragmented and unreliable.

In a 1971 essay, Cheever hailed F. Scott Fitzgerald

for his “acute awareness of the meaning of time,” with characters who “lived in

a temporal crisis of nostalgia and change.”

By the end of this story, the crisis that Neddy

Merrill has been denying becomes increasingly apparent, despite his impulsive, startling decision to recapture his youth by swimming the eight miles from the

Westerhazy’s pool to his own.

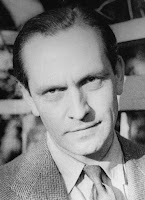

I haven’t yet seen the 1968 film adaptation of thisstory, but it’s hard for me to imagine a better actor to portray Merrill

onscreen than Burt Lancaster (in the image accompanying this post).

Two

decades into his film career, the Oscar winner still showed the amazing

physique he had achieved as a youthful acrobat. But few actors were better at

depicting the complexity and insecurity below this kind of magnetic presence

than he was.

Almost as soon as Merrill has conceived his almost

surreal ambition, Cheever is undercutting him as a figure of epic

self-delusion:

“He had made a discovery, a contribution to modern

geography; he would name the stream Lucinda, after his wife. He was not a

practical joker, nor was he a fool but he was determinedly original and had a

vague and modest idea of himself as a legendary figure.”

The irony will only mount as Merrill stops

periodically at one party after another, in the course of which he is not only

stopped by one hostess but “slowed by the fact that he stopped to kiss eight or

ten other women and shake the hands of as many men.”

Midway through his swim (after, not so coincidentally,

about a half-dozen drinks), a storm breaks out, and Merrill’s temporal

perceptions become progressively unsure. A neighbor had bought Japanese

lanterns “the year before last, or was it the year before that?” It’s supposed

to be midsummer, but Merrill finds himself shivering, as if it’s already

autumn.

Before long, he is finding a less hospitable landscape:

neighbors’ properties overgrown with weeds and the doors locked; jeering by

passersby as he crosses a highway barefoot; sneers by another hostess at this

“gatecrasher”; and remarks and gossip he doesn’t register about his

“misfortune.”

While the story is seen entirely through the

consciousness of Merrill, the voice of Cheever slips through at times, as when

Neddy wonders if he was “losing his memory” or if his “gift for concealing

painful facts let him forget that he had sold his house, that his children were

in trouble, and that his friend had been ill?”

By the end, Neddy has been

exposed as an alcoholic, a philanderer, and a spendthrift whose financial ruin

has destroyed his family and left him friendless and locked out of his suburban

paradise.

Like the Lucinda River, alcoholism runs like a

subterranean stream in a number of Cheever stories, such as “Reunion” and the

novel Falconer. But seldom has the psychological dissolution it

unleashes been rendered with such irony and phantasmagorical brilliance as in

“The Swimmer.”

Cheever shared far more than a thirst for liquor and

an equally desperate quest for grace with Fitzgerald: Both also have tempted

filmmakers to create on-screen visual counterparts to prose whose shimmering

effects are felt primarily in the imagination.

So it was with The Great Gatsby, and so it was in

the late Sixties when the husband-and-wife screenwriter-director team of

Eleanor and Frank Perry tried to adapt Cheever’s tale of altered consciousness.

Frank Perry was fired midway through, and even a young Sydney

Pollack, hired to complete filming, couldn’t steady a production that had

become as uncertain as Neddy’s nautical journey home.

Despite a pleasant on-location experience in Westport,

CT (where Cheever made a cameo appearance at a poolside cocktail party, where,

Neddy-like, he marveled at a “terrific 18-year-old dish”), the author loathed

the finished product of the troubled production. (I’ll have to wait till the

next time it comes on TCM to assess the merits of his complaints.)

In a way, Cheever is the missing link between F. Scott

Fitzgerald and Mad Men (just a few of the many literary references on the late, great series examined in Jenny Tighe's post on the "Bloomsbury Literary Studies" blog). It’s apparent symbolically even in the opening

credits of the classic AMC series, in the vertiginous fall suffered by its main

character.

Mad Men’s showrunner,

Matthew Weiner, took his time (seven seasons) showing how ad man Don Draper hit

rock bottom, just as Fitzgerald took an entire novel to detail the warped

promise of its once-dazzling protagonist, psychiatrist Dick Diver.

In contrast, Cheever compressed the story of Neddy

Merrill, but the result is the same in all three cases: men fooled by the

shimmering surface of the American Dream, with not enough intestinal fortitude

to survive the loss of their illusions.