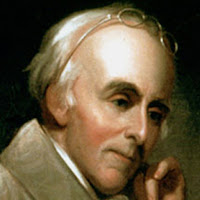

Dec. 24, 1745—Benjamin Rush, a doctor at the forefront of intellectual and reform movements in the first four decades of the American republic—including signing the Declaration of Independence—was born in Byberry Township, Penn. (The date used here was according to the Julian Calendar that prevailed in England and its colonies at the time.)

Last week, I wrote a post about another underrated Founding Father: John Jay. But, in its way, Rush’s career was more varied,

more interesting—and more tragic. After all, how many other figures are

considered so crucial to the origins of abolitionism, prison reform,

psychiatry, eugenics, and substance abuse treatment—or been forced to put many

of his concepts into practice by treating his own mentally ill son?

As a member of the Continental Congress whose

activities ranged across multiple fields, Rush may have been surpassed only by

two friends who also signed the Declaration, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas

Jefferson. He embodied the best notions of the American Enlightenment for his belief in republicanism, toleration, scientific progress, and the elevating impact of education.

Yet, though regarded as the most famous and brilliant American

physician of his time, his renown faded somewhat in the two centuries after his death

for three reasons: his relatively brief political career, a longtime lack of

access to his copious writings, and out-of-context misunderstandings about some

of the more controversial aspects of his medical career.

In recent years, Rush has become the focus of some

long-overdue scholarly attention. First, Stephen Fried’s highly acclaimed biography of the doctor appeared two years ago. Second, the current

COVID-19 pandemic has led scholars to re-examine Rush’s controversial role in a

major epidemic of his career: a Yellow Fever outbreak in Philadelphia.

Though not the sole physician who signed the

Declaration, Rush was the only one to receive a university education in

medicine (the College of Philadelphia, then the University of Edinburgh).

From his late 20s on, he became active in politics: persuading the recent English immigrant Thomas Paine to call his incendiary pro-revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense; discussing how to advance the new movement while dining at Philadelphia’s City Tavern with John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington; and, after signing the Declaration, leaving his pregnant wife behind to serve as physician in chief of the military hospital of the Middle Department of the Continental Army.

In the latter frenetic period, Rush was a trusted

confidante and admirer of Washington: witnessing him clutching a page saying

“Victory or death” (the watchword for the attack) before crossing the Delaware at the Battle of Trenton;

treating the dying Gen. Hugh Mercer at the Battle of Princeton; slipping out of

the clutches of the British after being briefly captured at the Battle of

Brandywine; and writing an essay on

improving soldiers’ medical care that Washington pressed on his

subordinates.

But before long, Rush would also display the habit of

caustic, impolitic and sometimes indiscreet writing that attracted a host of

enemies. He became appalled by medical treatment of soldiers at the hands of

his superior, John Shippen, then at the Continental Congress for clearing him

of wrongdoing.

Rush made an even more significant enemy when he

penned an anonymous letter to Patrick Henry that was critical of Washington. Henry disregarded Rush’s plea to burn the letter immediately,

instead passing it along to the general. Washington was so angry at Rush’s

duplicity that the doctor felt compelled to resign his post.

In the 1780s, students rather than soldiers became the

primary focus of Rush’s attention. At the University of Pennsylvania, he served in a number of capacities over the years, including professor of

chemistry, professor of the theory and practice of medicine, and professor of

the institutes of medicine and clinical practice. Unlike many of the other

Founding Fathers, Rush was egalitarian in outlook, believing that a good

education should be enough to qualify candidates for public office.

All the while he was lecturing to enthralled students (more than 3,000 in his 45-year career),

Rush was maintaining a vigorous publication schedule (an estimated 85 significant publications, including the first American chemistry textbook) and becoming what would

now be thought of as a public intellectual on health and educational matters:

* He founded Dickinson College in Carlisle,

Pennsylvania (1783), Franklin College (now Franklin and Marshall) at Lancaster (1787),

and the College of Physicians (also 1787);

* He sought, at Pennsylvania Hospital, the nation's first hospital, to get better

funding for the mentally ill, and to stop the shameful practice of warehousing

them;

* He called for treating addiction as a medical

problem years before this became standard practice;

* He sought to reconcile two modes of beliefs that he

heartily embraced: rationalism and religion;

* He proposed a national system of public education

with a federal university to train public servants; and

* He advocated for the education of women.

On top of all these efforts, Rush not only called for

an end to slavery but, differing from the conventional wisdom of the time,

declared that there was nothing physically different about African-Americans

that would prevent them from achieving as much as whites.

Unfortunately, Rush endangered his reputation for

being in the vanguard of progressive thought—not to mention his professional credibility—by his role in Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic of 1793. (A thorough but critical examination of his role is provided by Robert L. North's "Benjamin Rush, MD: Assassin or Beloved Healer?" in a 2000 article for the Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings.)

At the start of the epidemic, Rush’s standing with the

public actually rose, as he was one of the few physicians even to stay in the

city to treat patients. But no approach he tried with patients seemed to work.

At this point, recalling a 1744 medical paper, Rush

hit on the expedient of bloodletting and purging. Even when that didn’t work,

he only resorted to it all the more often. (Ironically, Rush had stumbled onto

they key to yellow fever outbreaks—his notes refer at one point to “Moschetoes”

that were “uncommonly numerous”—but he never made the connection to the

disease’s origin.)

William Safire’s novel Scandalmonger (2000)

takes the viewpoint of Rush’s enemies by depicting him as a "murderous

quack" and "Dr. Death," but it leaves out an important bit of

context: Nobody else at the time had the least idea of what caused the

disease. But the damage to the esteemed doctor’s credibility was done. He

felt compelled to withdraw from some of his positions, and even his practice

suffered for a time.

Adams’ appointment of his old friend as Treasurer of

the U.S. Mint enabled Rush to rebuild his reputation even as he re-entered public

service. He remained wed, fatally, to his old idea on fever—when stricken with

typhus in 1813, he instructed that he be treated through bloodletting and

purging—but at his death, a grateful populace turned out en masse to pay tribute to one

of Philadelphia’s most honored citizens.

In his 2018 biography, Rush: Revolution, Madness,

and Benjamin Rush, the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father,

Stephen Fried explained how the physician-patriot’s intimate connection to the

leading lights of his time led to his relative undervaluation by decades of historians.

At his death, descendants of several prominent families had reason not to have

his correspondence or journal entries cited by biographers--materials that would have confirmed his central in the American Revolution:

*Jefferson’s family did not want airing of his

skepticism about the divinity of Christ—opinions that could have been

misconstrued to suggest he was an atheist—or his request to the doctor for the

best way to treat his hemorrhoids;

*Adams’ descendants were sensitive about revealing

the President's anguish over a son’s descent into and death from

alcoholism—a pattern that repeated itself with one of the children of John Quincy

Adams; and

*Rush’s family was not keen about divulging

the reason behind his disrupted friendship with George Washington, now firmly

established as the Father of His Country.

Even as he struggled with the personal tragedy of his son John--a physician who, after killing a friend in a duel, became so mentally unstable he needed to be placed under his father's care-- Rush, in his last decade, performed one of his greatest services to posterity by relentlessly urging old friends Adams and Jefferson to repair the breach that had developed because of their competition for the Presidency.

That reconciliation not only helped heal old wounds between the

proud old patriots but led to one of the most extraordinary bursts of

correspondents among two ex-Presidents—creating a treasure trove that scholars

have used since to better understand the extraordinary generation that produced

such revolutionaries as Adams, Jefferson and mutual friend Rush.

No comments:

Post a Comment